A few years back I found myself on camera with Regis Philbin on the quiz show “Who Wants to be a Millionaire.” A few days prior to that encounter, a factoid learned when I was sixteen drifted into my brain during a trivia-cramming-induced stupor.

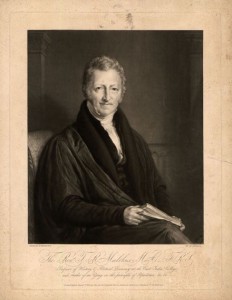

The information that floated back concerned the 19th century Englishman Thomas Malthus and his Iron Law of Economics. In my dream state, I had imagined myself saying something like, “Well, Regis, I learned in high school history that Parson Malthus said poverty was linked to child-bearing and that improved family finances were inevitably set back by the arrival of the next child.”

To my utter astonishment, one of the questions actually posed was about the social behavior promoted by Malthus. The correct answer and my final choice was “birth control.”

While I rarely think any more about my fifteen minutes in Regis’ hot seat, I do sometimes think about Malthus and his philosophy.

Recently I have had more reason to think about Malthus and his ideas, although I concede the irony that the correct answer in a television trivia game is offers a critique particularly relevant today.

We need to revisit such ideas as we try to climb out of an economic hole dug deep over decades. We need to consider such ideas as we parse the political “discourse” that marks this election year. We need to examine the claims of GOP candidates and analyze their facts from every possible vantage point. Before we condemn the performance of the current administration as it struggled to halt the financial freight train already accelerating downhill at the time of the last election, we need to determine whether that freight train has been slowed and whether it now travels on a more secure track toward prosperity for all and not just for the “one percent.”

Recently, ABC journalist Robin Roberts interviewed Coca-Cola CEO Muhtar Kent about his claim that we are in the “Century of the Woman.” Kent reckons that true equality for women in America on every level would contribute to increased productivity and a significant rise in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

At the conclusion of the interview I seemed to hear a deafening chorus of “DUH.” The voices were not all female, or even Democratic. They were, however, all coming from the same position of rationality, modernity, and pragmatism.

This perception of the economic potential of women, however, apparently is not shared by the GOP-dominated Congress. The House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform (a committee chaired by a man and comprised of eight male Representatives) convened a panel to discuss the inclusion of contraception in health-insurance plans. Their first panel was entirely male; the only two women invited to participate mouthed the policies of their fundamentalist Christian institutions.

Quite sensibly, the Democratic women walked out on this travesty of a hearing. Later testimony by Georgetown law student Sandra Fluke—and Ms. Fluke’s personal integrity—were famously inspiration for Rush Limbaugh’s abusive rhetoric.

Let us, however, return to the good Parson Malthus. In 1798, Malthus published the first edition of An Essay on the Principle of Population as It Affects the Future Improvement of Society.” It was a pessimistic tract, one that caused Scottish essayist Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881) to describe economics as “the dismal science.” In the words of Robert L. Heilbroner (and I quote from the paperback copy of The World Philosophers I bought for that high-school history class in 1967), Malthus averred that, “there was a tendency in nature for population to outstrip all possible means of subsistence… Rather than headed for Utopia, the human lot was forever condemned to a losing struggle between ravenous and multiplying mouths and the eternally insufficient stock of Nature’s cupboard, however diligently that cupboard might be searched.”

Am I a pure Malthusian? No, certainly not.

Do I think that a nation whose laws and social mores are designed entirely by men of a limited and fundamentalist religious outlook can compete economically and politically on the global stage? No way.

Do I think that the United States of America can move ahead by obsessing over ways to ordain adult behavior in bedrooms and proscribe women’s reproductive decisions? Absolutely not.

The effort of half of the population to exert absolute control over the other half of the population cannot contribute to a more economically powerful country. The claim of a dwindling majority of one race or religion to privileges and truths they deny members of other races and religions is not going to serve us now or our children and grandchildren in the future.

We need to hear voices and respect ideas that express all points of view. We most of all need that discourse to be a search for common ground rather than a battle for ultimate supremacy.

It is an election year. We can regard our votes as an opportunity to pull together as a nation or as a chance to disenfranchise as many people as we can in the hope that “we” prevail and “they” lose. Let’s just think about the implications, though, of what happens when we turn significant numbers of Americans into losers instead of opening success to all of us.