Ruins. Antiquities. The bones of the dead.

Italy is a place where one culture layers on another, razing, reusing, raising new structures for new orders. Italy has commoditized her archaeological past since long before she was unified as a nation in 1860. Romans collected and copied works of Greek art. Greek, Roman, Egyptian relics were collected, reconfigured, reused, displayed and copied, an activity that both brought about the Renaissance and expanded it. From the 17th century on, classicism, both as a focus on the antique and the accomplishments of the High Renaissance, was revived with the prefix “neo-“. Modern desperation to preserve the past, for its intrinsic worth as well as its tourism value, is part of that story, too.

We had ruins in mind as we planned our excursion and kept watch on the weather reports: Pompeii and Herculaneum, the National Archaeological Museum in Naples, Paestum at the southern reaches of Campania. Expecting a string of cloudy, perhaps damp, mostly mild days, we were confident that we’d knock more than a few items off the bucket list. The best-laid plans…

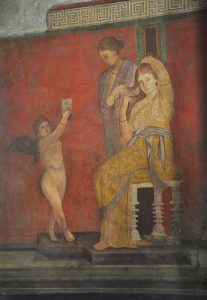

The weather turned cold and snowy and hampered any activity in the out of doors. Or the indoors. It was cold everywhere and even restaurants were dragging in space heaters. Didn’t pack for that. Then there were the extreme variations in the experiences offered by different locations and institutions. Didn’t do the mental packing for that, either. At Pompeii one fights through crowds of visitors and a phalanx of tchotchke vendors. The ruins are hardly marked with any kind of signage and the damages of time, weather, morons and vulgarians are in constant evidence. Relics extracted—or should I say pillaged—from the scavi (the excavations) have mostly been shipped to the National Archaeological Museum in Naples and remaining treasures, like the paintings in the Villa of the Mysteries, are left unguarded and under attack from the impulsive fingers of children as well as the cruel actions of vandals.

The Naples National Archaeological Museum, which one would expect to be a jewel in the crown of Italy’s collections, is a drafty, echoing, and ill-kept heap built as a cavalry barracks, later transformed into a university building and finally adapted to the needs of a museum in 1750. (Since the relocation of paintings and other art works to the Capodimonte Museum in 1957, the building has been devoted entirely to archaeological collections, especially objects found in Pompeii and Herculaneum. There are also the classical sculptures that constitute the collection known as Farnesiana and some Egyptian things.)

On walking through the entrance one is assailed by “official tour guides” wearing IDs, who seem more like the hucksters on the steps of Termini Station in Rome who try to get you into their fleabag hotels and pensiones. Guards were in most rooms, and were mostly focused on newspapers or cell phones. The “café,” that place where one expects to be able to rest over an overpriced espresso and not-very-fresh cornetti and revel in the memory of treasures seen, is an empty hallway with some vending machines. And no seating.

NAM houses true marvels—in particular mosaics, including the Alexander Mosaic, wall paintings, and the Farnese sculptures—but the installations are mostly sloppy and haphazard. Labels, such as they are, were difficult to read and didn’t really help us understand the layout of the villa or culture of the times. Three of the seven galleries devoted to Herculaneum’s Villa of the Papyri were closed so we didn’t learn anything about the papyri, the vast library that was almost entirely lost. I do know, though, that technology is making it possible to “read” some of those incinerated scrolls.

Installation and interpretation of the wall paintings was much better, but difficult to follow. I struggled to grasp where the houses had been, what the social and economic standing of the owners had been, and how they fit into the sequence of styles (or what, for that matter the sequence of styles was). The Farnesiana on the ground floor was dreary, a lot of whitish marble in rooms painted a dirty cream. I could see that much of the sculpture has been repaired and/or restored repeatedly over several centuries but labels mostly ignored how those changes affected the authenticity and aesthetics of the works.

So we left bummed. And very, very cold.

By way of contrast there was the Museo Archeologico Provinciale di Salerno, to say nothing of the scavi and museum at Paestum.

Given the freezing sleet that appeared to be our meteorological lot on this trip, we focused more on local attractions. As we climbed up via San Benedetto, stopping occasionally to draw smiley faces in the snow covering car windshields, I felt discouraged. Naples had been such a disappointment—and if a huge, important tourist-draw like was so unsatisfactory in terms of presentation and education, the place we were headed was likely even worse.

MAPdiS, however, is a gem! The building dates to the Romanesque era and was part of a monastery. It went through a number of unhappy incarnations and then in the late 1920s was dedicated as a local archaeological museum. An extraordinary number of objects of exceptional quality and interest are gorgeously installed in handsome and well-lit cases. Labels are helpful and the English-language translations are excellent. The presentation is chronological on the ground floor (starting in the Neolithic period and working up through the late Roman Empire). The first floor was dedicated to the discoveries from Fratte and included fascinating computer animations on such subjects as making pots and burying the dead. In the back, a table and drawing materials encouraged children to think about what they had seen—or just have a good time. A particular delight was a small exhibition of paintings and tiny “sculptures” (inspired by Legos!) by Stefano Bolcato.

Our designated day in Paestum—and our last day in Salerno—dawned partly cloudy and less cold. The drive was easy, not unpleasant. Plenty of parking, hardly any people. And the air was warming and the clouds were clearing. A tour of the museum provided further proof that NAM was an aberration. Or an indication that there is some problem specific to Naples. The only convenient lunch establishment adjacent to the scavi was mobbed with American college students—wonderful kids from Minnesota and Quinnipiac College in Connecticut and other locals—so the proprietor set us up a table next to the snacks and candy racks. Finally we headed to the ruins.

And there were no people. Well a couple here, a cluster of five there, but the scavi were largely empty. No one ambling into my photographs, no long waits for those “decisive moments” when the scene is perfectly unpopulated. We strolled. Limestone gleamed in the slanting rays of the sun. The sky was truly blue. These were the buildings I had learned as the epitome of Doric style. This was a space that was a Roman as it was Greek, and entirely something its own.

The ruins that saved our vacation from ruin.

Great writing, Ellen! Preps me for the crowds at Pompeii, ameliorates my loss at not having time for the NAM, and makes me regret even more not getting to Paestum. Thanks for the glimpses with the great cultural and historical perspective! Glad you have a ‘save the day’ attitude towards traveling!