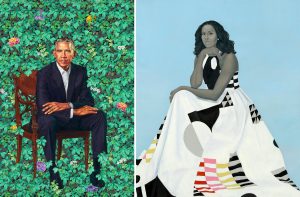

On February 12, 2018, the portraits of the 44th President and First Lady of the United States were unveiled. How do I like them? Let me, as it were, count the ways.

The paintings are modern. The artists who made them (Kehinde Wiley, b. 1977, and Amy Sherald, b. 1973) are young-ish. Both are figurative painters and the art they make is historically informed, politically aware and edgy in terms of color, form and space. The images are realistic but do not rely on the pat illusionism of the academician. These are not photographs remade in pigment.

The paintings are dignified. Expression balances with certainty and stability on that thin wire between flattery and likeness, between propaganda and characterization. Both artists well understand that they are providing for the future something different from the countless photographic and videographic images that document the Obama administrations.

In choosing Wiley, Obama chose an artist who like him is the son of an absent African father and an American mother. Both men have lived as outsiders, Wylie as a gay black man, Obama as an American Christian child in a Muslim community in Jakarta, a black youth living with his white grandparents in Hawaii, and the first African-American to enter that bastion of white maleness that is the Oval Office.

About a decade different in age, Sherald and Michelle Obama felt an affinity, “an instant sister-girl connection.” Sherald expressed her affection for her subject, saying “You exist on our minds and hearts in the way you do because we can see ourselves in you…an idea—a human being with integrity, intellect, confidence, and compassion.”

Just about every writer has raised these important points. I have other, better reasons for my affection. When I look at the portraits I hear the immortal words of Uncle Morton (in Rembrandt Takes a Walk) as he regards the eponymous self-portrait in his collection: “Beautiful isn’t it? Every time I look at it, I discover something new in it.”

That leafy backdrop behind Barak Obama? Well, yes, it does remind me (and so many others) of the ivied wall at Wrigley Field. And that makes me think of Chicago. The black president’s game, though, is hoops, not America’s pastime. The flowers tucked in the greenery—African blue lilies for his father’s Kenya, delicate jasmine for Hawaii where he was born and spent so many years, and chrysanthemums for Chicago, his political birthplace—are the kind of symbols one might find in art created by the Old Masters of western European art.

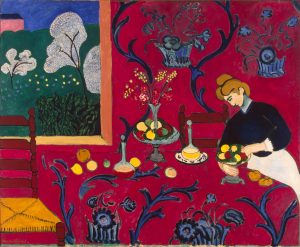

I am drawn back to the ivy. It fills a continuous plane from top to bottom, obscuring any evidence of the perpendicular relationship of ground and wall. This is all Cézanne by way of Matisse. Look at the glorious red pattern of Matisse’s The Dessert: Harmony in Red (1908) and the way the cloth denies the edge of the table and is indistinguishable from the wall behind and under the ladderback chair at the left. I’m pretty darned sure Kehinde Wiley looked at that.

Is that ivy, though? I’ve been to Wrigley Field; the ivy there has a different leaf (and I googled it just to make sure). Is that… No. It couldn’t be…poison ivy? Leaves of three, let it be? It’s not Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia); we have masses of that climbing the retaining wall out back. It’s not a Common hop tree (Humulus lupulus); no dangling flowers and the leaves are not serrated.

Would Wiley have placed the first black president in a bed of Toxicodendron radicans? The man looks like he has just returned from the Oval Office, pulled off his tie and taken a seat where he continues to ponder the problems that can never be left at work. That man seems oblivious to the vines that encroach, not reacting to any itch-causing oils. He is at home in this threatening thicket that makes me see American politics and society.

Michelle Obama and the black and white and color-block architecture of that dress fill the wide vertical of Sherald’s canvas. The blue background—subtly textured, almost imperceptibly darker above than below—evokes the sky. The First Lady is isolated against that space. This is an old trick, a means of showing respect and admiration, a subliminal suggestion that the figure is on a higher plane. Her form is a pyramid, impossible to discompose, destabilize or disregard. This is Michelle Obama as solid as the earth and at its heights.

Her bespoke dress (from the Milly Collection by Michelle Smith), inspired by the Gee’s Bend quilts, is ordinary in many ways. It is made from practical and comfortable cotton poplin—the kind of fabric that would have been incorporated into many quilts. Its practicality reminds us that Michelle Obama is a prudent woman, someone who understands that value is defined by usefulness given cost. Yes, the colors and black and white have that de Stijl flavor—but this is not Yves Saint Laurent channeling Mondrian; this is an entirely different imagination of a distinctly female kind.

Above it all, Michelle Obama’s countenance is radiant, serene, introspective. The gray-scale erases skin color. The technique evokes the illusionism of carved stone limned in grisaille, a medium favored in 15th century Netherlandish art. All evocations of transcendent womanhood come to mind: the marble goddesses, polychrome Madonnas, queens in Europe, heroines of literature, stars of cinema.

There is one last reason I must count. Particularly in Europe during the 15th and 16th centuries, portraits of couples were painted as pendants. They were separate works with separate frames, but they were intended to hang side-by-side. Often the background is continuous across both; typically, the figures turn toward each other in implicit unity. One things of Raphael’s portraits of Agnolo and Maddalena Doni for instance.

When I saw the paintings together, him on the left, her on the right, I was struck by that same physical connection despite the extremely different styles of the artists. What I thought of were the portraits by Veronese made in 1552 of Livia da Porto Thiene and daughter Deidamia, whom I visit often at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, and her husband Giuseppe da Porto and their son Leonida who abide far away in the Palazzo Pitti in Florence, Italy. These life-size paintings were originally installed in niches in a wall in their home in Vicenza, so that unsuspecting visitors might imagine the family were all come to greet them.

It is as though Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald at different times and in separate studios both imagined their subjects as a pair: individual, dissimilar, independent yet connected by their values, their commitment, their love. This couple, President Barak and Michelle Robinson Obama, welcome us to the idea that greatness is possible through the grace of decency and love.