As the Reverend’s 80th birthday was coming up, her sister Belle called and asked a favor: would I be willing to print off a copy of the family genealogy for a gift? Like the one she had received from her kids on one of her own big birthdays?

Reverend and Belle are the closest once-removed cousins to me on the family tree, the lastborn children of their generation while my sister and I are the firstborn in ours, and they have always been my favorites. Of course I would create a book for her. We agreed that it would be in Belle’s hands not later than September 15 in anticipation of the September 17 celebration.

I hadn’t done much with that research in ages, distracted as I was by my Dear One’s far more interesting Lithuanian roots. I knew there would be errors to clean up in the files, duplications, typos, this and that. I also thought this the right moment to grow it a bit, starting with the entry for the Reverend herself.

One thing led to another.

I pushed back the Brown family—Rev and I share that middle name. I discovered the Chandlers, the family of Sarah who married a Phelps who married a Fields who married, several generations down, a Greeley, a family I know much more about. The earliest Chandler was a Thomas born in 1475; he’s my 13th great-grandfather.

Time, however, was barreling on and however much fun is to pile up generations, I needed to get the book put together, take it to Kinko’s, and get it shipped north. It would take a while to arrange the pieces and play with fonts offered in the software. Gotta love that combination of Edwardian Script ITC copperplate and Garamond.

Rev loved it. Belle was tickled too. The project complete, I went back down the rabbit-hole that is genealogical research. First, I started finding the errors and typos that lard Rev’s book, but of course the best proofreading is always done after the document is shipped off. Then I returned to less familiar genetic lines. There are so many branches. My ancestral tree looks rather more like a patch of kudzu, so fruitful were my progenitors and so full it is with marriages between cousins, uncles and nieces, and remarriages to in-laws.

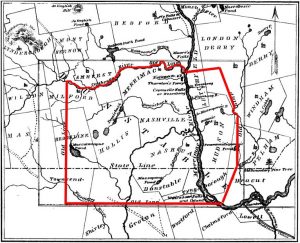

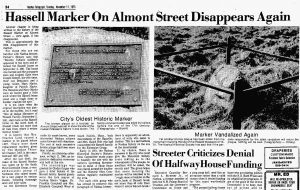

Eventually I landed up on Richard and Anna (Perry) Hassell of Dunstable in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, which is to say modern-day Nashua, New Hampshire. The little green Ancestry.com leaves included a newspaper clipping from the Nashua Telegraph dated 11 November 1975. The article described the vandalizing of a memorial to Richard and Anna Hassell, who, along with their son Benjamin and a neighbor Mary Marks, had been massacred by Native Americans on 2 September 1691.

Good thing Anna and Joseph were among their five children away at the time. (That’s what I mean about tangled connections: I descend directly from both offspring.)

The Hassells aren’t my only ancestors to die in the French and Indian Wars, but right now they are the only ones I know of who were civilian casualties.

Yet I had to think about that moment. In 1691, Dunstable was the frontier, the edge where white colonists were living in immediate proximity to Natives. In looking for some idea of what tribes were indigenous to that specific area, I found “Indigenous New Hampshire.” I scrolled down to Context of Violence and read the following:

But peace was difficult to maintain when ranging settlement cattle, swine, and dogs ravaged the Indian cornfields; when the Indians were forced to abandon their homes and their ancient hunting grounds by the ever-increasing numbers of white settlers who were constantly moving into the rich and resource-filled frontier of New England; when unscrupulous means were used to “purchase” Indian land; when white man’s rum wreaked havoc among the Indians; when the signing of “submissions” and covenants was required of Indian leaders […]; when trade and peace agreements were broken as often as they were made; when powwowing was forbidden (1646) as worship of “falce gods” and “the devill”; when peaceful Indians were jailed for crimes they did not commit, hung in public, sold into slavery, and kidnapped to be sent overseas for show-and-tell spectacles; and when Indian scalps fetched a handsome bounty. Neither was peace easy to maintain when both the New England colonists and the French resorted to using “the devil to destroy the devil,” or when white troops descended on Indian villages and campsites killing and maiming people and burning the crops which were to stave off the hunger of the long New England winters. There is ample evidence for all of the above – and much, much more (Piotrowski, Thaddeus. The Indian Heritage of New Hampshire and Northern New England. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company Inc., 2000., p. 14)

The fact is, the majority of my ancestors belonged to the first wave of invasion in the three or four decades that followed the anchoring of the Mayflower in 1620 off what is now Plymouth, Massachusetts. My ancestors helped create the system of government that systematically expelled the indigenous populations from their lands and decimated their numbers through the inadvertent and deliberate use of germ warfare.

In short, my ancestors were brave and inventive souls, moral in religious terms, pillars of their communities, and good parents who raised some admirable children. They also advanced an agenda of atrocities against the “savages” who lacked their concept of “civilization” and who, above all, did not believe in the Christian god who they believed blessed and protected and validated them in this life they had chosen.

What terror and pain Joseph, Anna, Benjamin and Mary must have experienced in those few moments as they met dreadful deaths. It was that terror—and the savagery of the perpetrators—that leading artists like John Vanderlyn tried to express in “documents” like the Murder of Jane McCrae (1804), which illustrated a particular event in Washington County, New York, in 1777.

There are no images, however, of the anguish so many Native Peoples must have felt as they experienced the scourges of influenza, measles and smallpox that European colonists brought with them. There are no expressions of the bleakness in their hearts as they faced the realization that the invaders with their guns and determination were destroying their world and expelling them from the place that their Creator had intended them to occupy for eternity.

So many of us discover discomfiting truths about our families. We ourselves have learned that even in enlightened Massachusetts, one of our ancestors owned a slave. We know that our people flooded into North America, shoving everything seen as an obstacle out of their way. They and various of their descendants became wealthy through tactics many of us would condemn today.

But be that as it may. The sins of the parents cannot be visited on the many-greats grandchildren. There is no restitution that can or should be levied on three hundred years or more down the line.

It does make you think, though. Long. Carefully. Objectively.

Mine didn’t go through?

Dear, dear Ellen,

Thank you so very much again and again for your chronicle of our family’s past, along with all the difficult times of our beginnings in America. We Prestons are so fortunate to have you guide us through our history. I want to keep in touch to learn all that you continue to discover about our family.

Much love, The Elder