In 1368, at the age of sixty-four, the poet and philosopher Petrarch settled into a home in the bucolic village of Arcuà in the Euganean Hills, just southwest of Padua. His daughter and her family joined him there; she ran the household while Petrarch studied, wrote and welcomed friends. Petrarch died in that scholar’s retreat in 1374 and is buried down the street by the church. We found our own retreat in Teolo, some fifteen to twenty kilometers north—depending on whether one rollercoasters the hills or circumvents them.

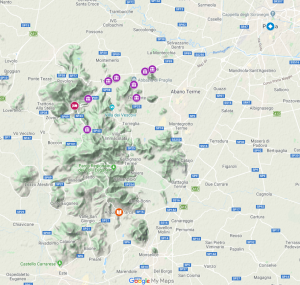

Teolo is both the hilltop village on Monte della Madonna and the commune that includes the frazioni or divisions from Feriole in the flatlands to Castelnuovo in the mountains. There are three main roads in and out of town. Via Euganea Teolo switchbacks downhill toward the plain and Padua in the east. Via Molare heads southwest; via Guglielmo Marconi plunges southeast into the heart of the hills.

Autumn is mushroom season in the Colli, said Jacopo, the server at the Bar-Enoteca-Ristorante La Piazetta, as we seated ourselves in the sunshine. What would we like? He could suggest pasta with four kinds of wild funghi and a glass of good red from the Colli. Fall is also the season for chestnuts and the Sagra dei Maroni organized by Il Comitate Feste Popolare di Teolo was in its second and final Sunday of October. That’s the Chestnut Festival organized by the Committee for Public Festivals in Teolo. Nuts roasted in immense ovens filled the air with charred sweetness. Regiments of tables weighted with plates of food filled the space I have taken to calling War Memorial Plaza for lack of a correct name. Families, couples, bicyclists and random folk emptied the stores of food vendors and children crowded around a puppet show, some quietly rapt, others dancing with glee.

The bells of the parish church, Santa Giustina Virgine e Martyre, are faintly tinny as they mark the hours; a neighborhood rooster welcomes each morning at seven. The windows in our bedroom and living room look due east; Each moment of each sunrise has its own colors and its own light, and the clouds caress the hills as they pass like Zeus, in the guise of a cloud, embracing Io, the Princess of Argos. The front windows overlook the Piazza Tito Livio and across the street to the Palazzetto dei Vicari (which now houses a Museum of Contemporary Art and tourist information).

It takes perhaps five minutes to circle the center of town—the area downhill from Santa Giustina, above the Museum and the three blocks that cross the main streets. Six or seven if one pauses to windowshop or read notices. A fruit and vegetable seller, butcher, general grocery and pharmacy on via Molare, where it curves to intersect via Guglielmo Marconi, constitute the main commercial district. A bus awaits bundles of bambini giggling their way out of the primary school on the hill above. The school grounds also provide overflow parking when a Feste is underway.

Italy’s bicyclists love the Colli and on a dry, sunny weekend swarm the switchbacks. It looked like the Giro d’Italia, pelotons a dozen strong and strings of eight or ten individuals everywhere we went, with no way of knowing what hid beyond the next bend. Occasionally hikers, or sedate walkers with their dogs, appear on the verges; cars and bikes jam the inadequate lots of the restaurants and bars.

The hills are abundant with sacred spaces and a history that reaches back to Roman times. The Casa del Petrarca has been preserved almost unaltered since the poet’s death some six-hundred-odd years ago. Number 15 in the Piazza Tito Livio, Domus Tito Livius, was built in the eighteenth century and saved and modernized in the last decade. On our twelfth and last evening, the setting sun sliced through the damp that had persisted much of the day. I turned from the panorama of sunset back toward the Piazza to find a rainbow—an arcobaleno—framing the town, iridescent above the war memorial, the church, the Colli and our little stone house.