Unless I want to be an Edie, Big or Little, in an ersatz-colonial Grey Gardens, I need to begin the process of emptying this house. We’ve been happy here. At least I think so. It is hard, indeed, to truly know what Dan was thinking about much of anything. Moodiness was his norm, easily upset and inclined to sulk.

Sometimes it was my words or intonation that set him off. Most often, it was the “bad thoughts,” the darkness resisting light that was the cause. We were a couple for nearly 39 years; married for thirteen of them. I think I knew him pretty well. I think I knew better than most whatever it was that he allowed to be known.

As I think is often the case, though, I am finding the bits he would not share, that he kept most successfully buried. I suspect I will find more detritus from his pain.

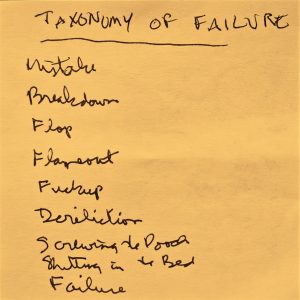

A Scrap Of Paper

The other day, a friend and I were packing up books in Dan’s study: mysteries, thrillers, gifts from me from the past decade or so, texts that defy categorization. Before books are boxed, they are fanned, in case money or love letters or unpublished poems or important clippings have been stored between the pages. A yellow Post-it note found its way to a shelf.

I read it. His handwriting. His words. Phrasing for a story? Or some kind of assessment about the stories he knew he would leave incomplete and unpublished. A “Taxonomy of Failure.”

It is a taxonomy and not just a list of synonyms. While all are self-referential, some are forgivable, like a “mistake.” Some—“flameout,” “breakdown”—suggest unsuccessful efforts, unmet goals, stars reached for but not grasped. Several are judgments of personal inadequacy: “fuckup,” “dereliction,” “shitting in the bed.”

And “failure.”

Who He Believed He would Be

Dan said he knew he wanted to be a writer by the time he was six years old. He had notable success, winning awards and publishing poems and fiction before he was out of high school. I typed up the notes he made for his obituary and he emphatically revised the sequence to place that earliest vision front and center.

When he contemplated and then began dialysis, he was clear about what he wanted. He wanted to feel better, have more energy. He wanted to finish writing and revising the novels he had been working on for years. Decades. Revisions that I had typed over and over and over. My great sorrow is that he was denied that heart’s desire.

Heart’s Desire

He wanted to become the writer he knew he was. He wanted to complete the work he felt he was born to do. I know he knew that he left that work incomplete.

My work, which was to care for him, soothe him, handle his dialysis, help him do whatever he needed to do, in the end, could not do that one thing.