We learned of the imminent opening of a museum dedicated to World War One from a cashier at a Carréfour market somewhere on the outskirts of Meaux as we headed into our final week in France. Her English was superb, but then, she said, she was half-English. Once settled into our gîte Milleroses, we tried to find out more. There is a poster for it, the Museum of the Great War 1914-1918, on the bus stop nearby. We collected brochures at the Office de Tourisme in Meaux. We searched the Internet for information and queried everyone we could find.

Information came out in drips and puddled in ever-changing configurations. Finally, a conversation with Flora Nicolas, Cemetery Assistant, and David Atkinson, Superintendent of the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery, brought details into focus. Work on the site was running behind and there was not a snowball’s chance in hell I would be able to witness the dedication or even be on the premises at that time. Mr. Atkinson made another comment that has stayed with me. In reference to the amount of publicity dedicated to the museum, he said, the border between Île-de-France and Champagne is more like an impermeable wall. On his side, practically nothing has been said; on Paris airwaves it’s been Musée de la Grande Guerre 24/7 for months.

The late Speaker of the House of Representatives, Thomas “Tip” O’Neill of Massachusetts, coined the phrase “All politics is local” decades ago. It’s true, and in France it seems that history no less than politics is also local. The British think of World War One in terms of Ypres and the Somme, the Canadians claim Vimy Ridge and Beaumont-Hamel, and Americans focus on the Argonne and Chateau-Thierry. The French, especially the denizens along the Front including the Saint-Mihiel Salient, the area around Verdun, and the Aisne-Marne, have different claims on the war, the battles and the suffering. Locality, or as the French say, pays, shapes memory, both historical and personal.

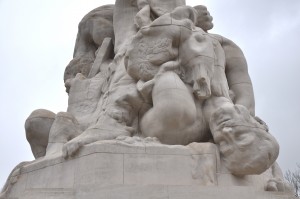

Tuesday afternoon, feeling somewhat at loose ends, my Dear One and I drove to the museum to see the massive monument, La Liberté Eplorée (Liberty Weeping) designed by American sculptor Frederick MacMonnies (1863-1937) that has towered over that location on the Route de Varreddes since 1932. The commission came from an influential group in New York City as a way to honor those who died in the First Battle of the Marne and was seen as a gift in exchange for the Statue of Liberty. MacMonnies began work in 1917; carving began in 1924; the monument, all seven stories of it, was not finished until 1932.

Bodies twist and fall, intertwining in almost indecipherable complexity. The work is huge; it is visible from a distance although one wonders what will be the case in twenty or thirty years when the newly planted oaks and lindens have achieved mature size. For all its Baroque spiraling, the monument has a front and makes the most sense from that point of view. An allegorical figure, female and mighty, howls toward the heavens as she clings to a nude figure, presumably the body of a soldier, lying backwards over her knee in a sort of pietà .

The total effect is something of a cross between The Departure of the Volunteers – The Marseillaise (1833-36) by François Rude (1784-1855), which is on the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, and Call to Arms (c. 1879), a bronze by Auguste Rodin (1840-1917).

The museum itself looks approximately finished.

The exterior, sheathed in metal and glass, appears to cantilever from the hill where the MacMonnies’ sculpture stands. It suggests an abri and explores notions of shelter, to my eye anyway, in various ways. At the same time it has a somewhat anonymous, early-21st century modernity that alludes to the early 20thcentury functionalism of the architect Charles-Edouard Jeanneret better known as Le Corbusier. That at least was my first impression as I stood in the cold and damp, sneaking pictures that a worker had told me were not permitted. (I suspect restrictions had more to do with security for the opening than any concern about the building itself.)

Photographs and a video on the Internet show an interior and displays that are more or less complete. The next twenty-four hours are likely to be a mad scramble of positioning labels, closing up cases, and making sure the toilets are all functioning. Landscaping, pavements and plantings, will likely continue for the next month or so. It’s an extensive piece of real estate and the museum and sculpture will anchor a new park. By spring I imagine it will look beautiful, as flowers and shrubs come into bloom.