Once upon a time there was a town called Independence, Missouri. It was famous mainly—at least to us denizens of the right and left coasts of the country—as the hometown of Harry S. “Give’em hell, Harry” Truman, 33rd President of the United States, the Vice-President who stepped up to lead a nation embroiled in wars in Europe and the Pacific after the death of President Franklin Roosevelt. He famously asserted “The buck stops here” and authorized the use of atomic bombs, “Little Boy” over Hiroshima and “Fat Man” three days later over Nagasaki. Truman presided over the Marshall Plan and the Berlin Airlift, and brought America into the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. He eked out a win over Thomas Dewey in 1948, watched both houses of Congress cede control to the Republicans in 1950, and made international interventionism national policy when our troops went to Korea.

This is the history that shaped my generation, the history that was even more formative for My Dear One, so off we were to Independence and the Harry S. Truman Library and Museum. A tourism booklet reminded us that Independence also offered the Truman Home, some historic buildings, the National Frontier Trails Museum, and quite a few eateries. There would be enough to fill up a lovely October day, we figured.

There is, in fact, too much to see and do in a single day.

Here memory goes back past the Civil War, the Missouri Compromise, back to the Santa Fe Trail at least. The atmosphere, however, is pure Heartland ordinariness. There are no stoplights in the historic downtown, just stop signs, polite drivers and ample free parking on the streets. Shops and restaurants buzz with friendliness. History has been preserved but not frozen; the feeling is contemporary not nostalgic; citizens seem to believe that the advantages of the new and an economy that includes tourism do not require destruction of the old or imply a reactionary yearning for the past.

Our timing was perfect. All federally funded locales were once again open; National Park Service rangers and staff of all kinds were happy to be back at work. Some options were so new that they aren’t fully present on the tourism guides.

The old Jackson County Courthouse, we were told, included the room where Truman once presided as “judge;” when we arrived there was also a sign that mentioned an art gallery. Talk about modesty! The building has been restored to its 1930s glory, fitted with up-to-date climate control, and is the new home of the Jackson County Historical Society. Sheriffs on duty eagerly provide the tour schedule and point out fascinating details like a “window” cut into a wall that shows a piece of original crown molding from the 19th century. Right below that glimpse of the past is an old phone booth—with a phone so ancient it would have taken you straight to a switchboard.

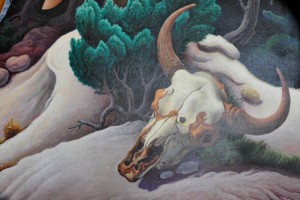

The present Courthouse is the most recent incarnation on that site, but at its core remains the original pre-Civil War structure, its exterior walls now shaping interior space. Archivist David Jackson reviewed the town’s history and the building’s architectural past. He walked us through the Truman courtroom and offices, took us upstairs to the original County Courtroom which has been restored to its original glory, and then to the Jackson Art Museum and its collection of portraits by native-son George Caleb Bingham (1811-79). The collection belongs to a couple of area restaurateurs and is on long-term loan. We moved from room to room, turning lights on and off as needed, and it felt like a gift given to us alone.

The Courthouse, while officially open, is very much a work in progress. Soon enough it will be not only the physical heart of historic Independence, it will bring under one roof a range of services and resources.

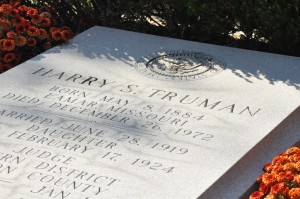

We spent only an hour at the Courthouse. We needed to eat before our 12:30 tour of the Truman Home, and took the sheriff’s and David’s recommendation to visit Elena’s. We passed up the daily special of a fried-chicken lunch for a vegetable and a taco wrap, which were simply delicious. After some circling—Independence does have several one-way streets—we arrived at the gingerbread fantasy built by Bess Wallace Truman’s grandfather George Porterfield Gates in 1867 and enlarged in 1885. This was where Harry and Bess courted for nine years, married, raised their daughter Margaret and died, Harry in 1972 and Bess in 1982. There was the time spent in Washington DC, while Truman was a senator, then vice-president and finally president, of course, but this was their home, their refuge, their happiness.

Park Service Ranger Norton (his last name starts with “C” but I cannot recall it), led our group through this place that has hardly been touched since the 1920s. There is no way the red-patterned wallpaper and green beadboard and woodwork could be “restored” to resemble period appearances; this was the authentic thing, a plain home for plain people left untouched, unimproved, because that was the way they liked it. The formal parlor in the front is a place for receiving guests; the den just off the kitchen, with its floor-to-ceiling bookshelves, is set up with his-and-her armchairs for companionable evenings of reading. The “television machine,” a gift from daughter Margaret, is stranded in a corner of the room that also houses the piano, positioned in a place where it is unlike ever to be used.

Visitors see only the ground floor, but Norton (Santa-Claus beard and long, tidy, honey-blond-shot-with grey braid) described details on the upper levels that spoke of the Trumans’ frugality. He clearly loves his job, admires the Truman family and the Truman grandson who remains the contact with the family, appreciates them and their home, embracing the obvious idiosyncrasies as well as maintaining an educator’s respect for objectivity and fact. Scrupulously attentive to the rules, he couldn’t allow us to photograph on the property, but he saw no reason not to photograph us standing on the front porch (that takes care of the picture that goes with this year’s Christmas letter) or get a snap of the silvery-green Chrysler Newport Truman bought only months before he died, and one or two more of the back of the house.

From there we went to the Library and Museum, swung past the Vaile Mansion, stopping only to take a picture, and arrived at the Bingham-Waggoner Estate in time for the last tour with thirty minutes left for a look at the Frontier Trails Museum.

Then there are all the places left unseen. And we still have our tickets for the Vaile Mansion and the Jail, Marshal’s Home and Museum.