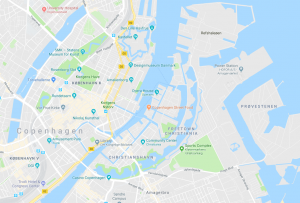

Christianshavn is a relic of 17th-century development. Thus its shape is that of a segment of a circle with the København Havn (the redundant “Merchants Harbor Port”) representing the chord and Stadsgraven Canal forming the arc. Originally a moat protecting the ramparts of the city’s ring of fortifications, Stadsgraven marks the beginning of the southern suburbs. One can stroll the ramparts from Langebro (the “Long Bridge”) in the southwest nearly to Nyholm in the northeast. The walk is interrupted by Torvegade, zigzags at Christiania and passes by the new location of Noma, considered by those who care about such things to be the “best restaurant in the world.”

Christianshavn was our home base for a week. Our apartment on Wildersgade was tucked in between Christianshavn’s two churches: Christians Kirke and Vor Frelsers Kirke (Our Savior’s). As one walks the neighborhood and even in the Old City, one spire or the other is almost always in view, beckoning with affection.

Distinct in many ways from Copenhagen is the free-living, pot-infused enclave called Christiana. In 1971 a group of squatters laid claim to an old barracks. Apparently, there are guided tours although I can’t imagine what for. It later turns out that I am two (three?) degrees separated from Christiania life. During a reunion dinner with TK, with whom I attended elementary school in Cleveland Heights, Ohio—so much history to cover since our last encounter in 1970—he mentioned that his sister’s daughter had lived in a burnt-out ambulance there for a while. His sister KK was a wild child; I’d love to meet the niece one day.

Travel writer and all-round annoying personality Rick Steves waxes rhapsodic about the charm and “fun” atmosphere of the place and the authenticity of the people. He seems to think a leisurely stroll through the enclave, anywhere except for the main drag and open-air weed market called “Pusher Street,” will provide magical entry into a community of original personalities who are self-reliant, independent and fantastical thinkers.

Today, some forty-seven years down the road, Christiania offers kaleidoscopic color, ratty flower gardens, found-object sculptures and a waft of eau-de-cannabis. There are quite a few cafés. Despite the back-to-the-earth culture, vegetables are imported, as the industrial past survives in the soil’s contamination.

If Christiania represents the wild and wacky right-brain side of Copenhagen culture, the great glistening lump of inkiness across the København Havn is its center of ordered thought. The Black Diamond, Den Sorte Diamant, is the 1999 addition to the Royal Library (Det Kongelige Bilbliotek) built in 1906. It is sheathed in black granite and dark-tinted windows; glass panels bring light that brings iridescence into the atrium that soars and curvettes.

Prior to our flight to Denmark, I had read Meetings With Remarkable Manuscripts: Twelve Journeys into the Medieval World by Christopher de Hamel (Penguin Press, 2016). Chapter seven is devoted to the Copenhagen Psalter, c. 1150-75, which is stored in their treasury. Read the book for many reasons but also read it for the travelogues. De Hamel’s trip up to the manuscripts area is an adventure:

You enter, threading past the bookshop (which also sells raincoats—very practical the Danish), into an atrium from which a very long and gently sloping escalator carries you unimaginably slowly up to the first floor. Here a motherly woman on the information desk directed me to the lifts behind me, up to the floor called ‘F Vest’ [F West]. You come out and turn left, along a glass-lined corridor to a door on the left marked ‘Center for Manuskripter og Boghistorie’, through which you find yourself in a kind of upstairs mezzanine gallery through which is the rare-book reading-room, overlooking the huge open space of the library’s atrium far down below. It is a bit like the top deck on a cruise ship, looking out over other decks (actually other reading rooms). Each projecting slightly beyond the next, on the various floors beneath. The hanging gardens of Babylon were probably something like this too.

We, of course, had no such privileges although we did ride the escalators and then the elevator to level G to take in the views.

The Black Diamond is oriented to the future; free computers and wifi invite visitors in. It includes expected resources such as the rare books and manuscripts collection but also a museum of photography and the Danish Jewish Museum. The new building faces the water lined by rows of modern office buildings; its plads is filled with deck chairs occupied by readers, sun-worshippers and nappers. The excellent restaurant on the ground level, Søren K (existentialist philosopher Søren Kierkegaard is the library’s patron saint), which de Hamel recommends, enjoys lively patronage.

Behind the Diamond, however, literally and figuratively, is the original 1906 structure that faces onto a walled garden designed in 1920, a refuge of quiet and beauty. Entrances from the Christiansborg Palace complex and either side of the Diamond lead one through small archways and porticoes; to step through them is to step into timelessness where the past extends to infinity and the future never quite arrives.

Two bridges provide us access to the Black Diamond—Torvegade and Langebro busy with bicycle and automobile traffic. Soon, maybe even this year, a new pedestrian bridge between the two will span København Havn.

For now, we see the spire of Christians Kirke and it is time to go home.