So many people seem to think a work of art in a representational style can be taken in at a glance. It is what it is, the way a photograph is a replication of whatever was parked in front of the camera. Ease of recognition, however, can result in profound misunderstanding. This is certainly a problem with headlines in newspapers and video clips on Facebook.

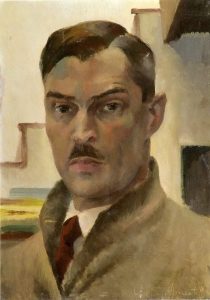

We in the art ed biz see this kind of inadequate or incorrect reading of images as a feature of “visual illiteracy.” The conviction that what one sees in a picture is exactly what the artist put there is at the root of the debate over the murals by Russian émigré Victor Arnautoff (1896-1979) painted in the George Washington High School in San Francisco in 1936.

Decoding Details

I get why people react so negatively at first glance or when offered only a snippet in reproduction.

We see a dead Indian, in the extreme foreground, at eye level as we climb the stairs. Black people labor in the fields, subservient in every way to their white overlords.

One might easily assume the whole is a paean to white imperial cruelty, genocide and the doctrine of Manifest Destiny. We might hear echoes of the words attributed to Union Army General Philip Sheridan (and repeated by American president Theodore Roosevelt) that “the only good Indian is a dead Indian.”

There is, however, more to Arnautoff’s murals that should be meeting our eyes. There are details to scrutinize and implications of design to examine. There is context to discover. His illustration of Washington’s life highlights the contradictions in our founding documents and the moral failings of our most venerated Founding Father, even if our modern eyes, however, don’t easily see this.

Before deciding that the murals are expressions of heinous attitudes, before destroying them, might we think further?

What was Arnautoff’s intention in taking on this subject? He was a leftist and we know that he intended to draw viewer attention to the abuses he recognized.

The Works Progress Administration (WPA) funded the murals. Does that make them objective representations of history or propaganda?

As works of public art, who owns them, who should preserve them and who has the right to destroy them?

The Value of the Collection

The Arnautoff murals, and his sculptures that decorate the exterior of the building, are among the earliest acquisitions in a remarkable collection.

The building itself was designed by Timothy Pflueger (1892-1946), leading Bay Area architect. Inside, the WPA commissioned murals by four highly regarded painters, Arnautoff, Lucien Labaudt (1880-1943), Gordon Langdon (1910-1963) and Ralph Stackpole (1885-1973). Arnautoff’s murals, done in the ancient buon fresco technique, are in the entrance to the school. The others are located in or near the library.

When a gymnasium and auditorium were added in 1942, African American sculptor Sargent Johnson (1888-1969) carved a bas-relief in 1942 celebrating athleticism along a wall at the edge of the playing fields. In the 1970s, Dewey Crumpler, an African American artist now teaching at the San Francisco Art Institute, created other murals that addressed the ethnic diversity of the community. (Crumpler also believes the Arnautoff murals should be preserved.)

Would it not be better to make Arnautoff’s murals—indeed the entire campus, including the building itself—the centerpiece of a unique community experience? Treat the artworks as the resource they are. Convene a committee of teachers and students, neighbors and scholars to explore ways they could or should be interpreted. Create a presentation and require every new student, faculty and staff member to see it and participate in a discussion about it. Make the presentation available online and at local libraries.

Censorship–or worse, the destruction of art that has met with disapproval–is not the answer. The murals—all of them and the sculptures too–could and should generate meaningful debate. They are perfectly positioned to initiate a critique of systemic racism in America and the lasting impact of imperialist oppression and genocide. These are conversations we need to have.

“History” is a quagmire of facts, lies and opinions. Students at George Washington High School in San Francisco have an unparalleled opportunity, through the Arnautoff murals and the other artwork, to see history come alive in a way that will connect them to the past, help navigate the present, and perhaps even change the future.