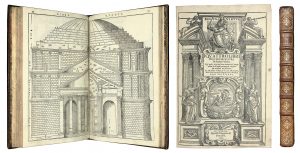

Andrea Palladio published I Quattro Libri dell’Architettura (The Four Books of Architecture), an inventory of his buildings, in 1570. Palladio largely invented the concept of the country home, conjoining the physical space of artifice with the metaphysical space of nature, liberating the spirit by replacing fortress walls with expansive fenestration. Thomas Jefferson, founding father, botanist, third president of the United States and amateur architect owned five different editions of the Quattro Libri. Palladio’s influence survives today in the ubiquity of the arched Palladian-style windows in mass-produced homes, architectural details intended to express good taste and high social position in middle-class suburbia.

Born in Padua and dying in either Vicenza or Maser, Palladio belonged as much to the Veneto as the fertile dirt of the plains and rhyolitic stone of the hills. If there is one single reason to spend time in the Veneto, in my opinion, it is to glory in the architecture of Palladio.

Our itinerary did not nearly cover the entirety of the Palladio trail of villas, palaces and churches found from west of Verona to northeast of Venice and the sweep of territory in between. Nor did I tick all that many buildings off the list but I am now four ahead of the one I had previously seen.

Teatro Olimpico, Vicenza, 1580-1585

The Treatro Olimpico, inauguratied five years after Palladio’s death, seems both beautiful and incomprehensible in photographs. What exactly was one looking at? How did this illusionistic proscenium—ostensibly the seven streets of Thebes contributed by Vincent Scamozzi—make sense in real space?

It is the oldest enclosed theater in the world and the semi-ellipse of seating, the cavea, with its thirteen deep risers, evokes the theaters of ancient Greece. Statues of the Academicians fill niches on the upper walls and the Labors of Hercules decorate the metopes–square panels–at the top of the proscenium. It is nonetheless a small space. Were it completely filled, the crowding would be palpable, audience members sitting hip to hip, toes nudging the back of the person directly in front.

The premier was Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex. In his opening speech Oedipus says,

Children, it were not meet that I should learn

From others, and am hither come, myself

I cannot being to truly learn this work is from others; I doubt any student would fully learn it from me. One simply must hither come oneself.

Villa Almerico Capra (the Villa Rotonda), Vicenza, begun 1655-56

This is the villa we teach in survey: the sphere in the cube, the ode to geometry, the dwelling that is oriented to the points of the compass, the seasons, the winds. It sits on a small rise and so seems to unite the earthly and celestial.

Palladio described the place and his artistic response to it: The place is nicely situated and one of the loveliest and most charming that one could hope to find; for it lies on the slopes of a hill, which is very easy to reach. The loveliest hills are arranged around it, which afford a view into an immense theatre…because one takes pleasure in the beautiful view on all four sides, loggias were built on all four facades.

What is so extraordinary in this home is the intimacy. Yes, it is grand and beautifully ornamented. The ceilings are very high. The rooms that frame the rotunda, however, are modestly scaled. A dining table in one has seats for about twelve ad fits snugly in its space. A living room, just to the right off the entrance, is inviting with its overstuffed furniture, family portraits, side tables and books. A candid photograph of Britain’s late Queen Mum is visible from the doorway and her smile invites a hug rather than awe.

Villa Emo, Fanzolo, probably 1558-1561

This apparently was the set of the film Ripley’s Game (2002) starring John Malkovich as Tom Ripley. The grand central stair features prominently in promotional photographs and trailers.

The Emo’s, minor nobility originally from Venice, were land barons of the first order and notable for their early cultivation of corn discovered in the Americas. According to Palladio, granaries were among the spaces linked to the main block by covered walkways. Polenta anyone?

One gets the feeling that the client, Palladio’s “Magnifico Signor Leonardo Emo,” was playing keep up with the Rossi’s in hiring the Veneto’s most famed architect and M. Battista Venetiano, a student of the Veneto’s most famed painter Paolo Veronese. This is not my favorite of Palladio’s villas, perhaps because of the self-consciousness I perceive. The rooms are dressed to impress. The architecture and the decorations pontificate rather than opening up a dialog with the setting and inviting the imaginative musing of the viewer. The villa, however, is meant to please the client above all.

Unlike the Villa Rotonda, Villa Emo is not a work of beauty in three dimensions. Like a stage set, the wow factor is a matter of curb appeal. When we walked in the gardens after exploring the interior, the structure’s posterior seemed completed but not refined, absent of any evidence that decoration ever had been applied.

Villa Barbaro (1554-58) and the Tempietto (1580-84), Maser

The Villa Rotonda is divine perfection. Villa Barbaro is where I want to live.

While looking forward and opening itself to the landscape that drops away before it, the villa creates a private space for the nymphaeum behind. Loggias either side of the main block provide access to the private quarters that extend either side of the main structure and terminate in service blocks surmounted by sundials, one marking the hours of the day, the other the houses of the zodiac. As with the roughly contemporaneous Villa Rotonda, functional spaces are on the ground level, domestic on the piano nobile.

The frescoes by Paolo Veronese created 1560-61 took my breath away. I had seen most of them in reproduction—heck, I took a graduate seminar in the art of Veronese at the University of Delaware in 1988 and had included them in lectures on Venetian art. I knew that the paintings created continuity from the interiors to the scenery outside. I knew Veronese had played illusionistic games with shadows, reflections of light and the dissolution of matter, but I didn’t really understand what that meant.

What I didn’t expect were the scars and gouges on paintings that had had not been restored. Apparently, an owner in the 19th century found the decorations too old-fashioned to be tolerated and scraped them down in order to replaster the walls. The current owner, Vittorio Dalle Ore, whose background includes directing films, viticulture and business management, and microbiology, committed to the resurrection of these extraordinary frescoes. One has been left damaged, an artistic cripple, perhaps to make the others sing in sweeter harmony.

Veronese painted the most wonderful dogs throughout his career. As we departed the house, a trio of Veronese pups waited in the loggia below, hopeful, I think, of a treat from someone in the ticket office. Veronese dogs. I want one so much.

My attention turned to a beautiful church kitty-corner from the villa across via Cornuda. I took a picture and I should have stayed. At the very end of his life, simultaneously with his work on the Teatro Olimpico, Palladio designed this Tempietto, a gift from the Barbaro family to the good people of Maser. Quite a special gift.

San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice, designed 1566; completed 1610

I had seen San Giorgio Maggiore thrice before, in 1975, 2004 and 2009, crossing the lagoon to climb the tower and explore the interior on that last visit. On our last day in the Veneto, a sunny, wonderful day that carried no hint of the floods that would inundate La Serenissima in the next few days and which, as of this writing, have not receded, I studied San Giorgio as our vaporetto crossed between the edge of the city and Giudecca and the church’s eponymous isle. Not for the first time I contemplated the interlaced temple fronts that constitute the façade. The geometries are so elegant and harmonious, the composition so surprising and inventive, no matter how often I encounter it.

When my Dear One suggested a visit to the Veneto, all I could think about was Palladio. How many of his buildings would be open in the days turning from October to November? (Most of them, as it turns out.) How many might we be able to see? (Only four, as it turned out, not counting various buildings in Vicenza we merely walked by.) Would they be as beautiful as the photographs I have studied for years?

Much, mucb, much more beautiful. Much, much more of everything.