Revolutionary Spaces leads with its mission statement: “Open History. Enter Democracy.” Today that phrase resonates as strongly as it might have at the establishment of our Union. Based in the Old State House and Old South Meeting House, the organization presides over archives, changing exhibitions, and a host of programs.

More Than Clothes

Last week Old South Meeting House hosted Threads Of History: Martha Washington And The Lives Of Eighteenth-Century Women. A quilt pieced from Martha’s dresses provided a point of departure for three scholars presenting quite different narratives. Fascinating!

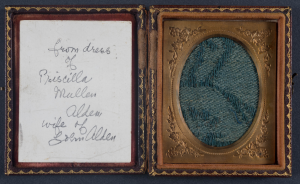

Martha’s frocks, and their value to her and her descendants, was nothing new at the end of the 18th century. A fragment of finely woven wool damask, dyed a deep green, came from a dress worn by Priscilla Mullins Alden (1602-1685). This woman, Priscilla Mullins Alden, arrived on these shores on the The Mayflower in 1620. She happens to be my ninth great-gran. I was not expecting her to join me at that moment.

It Happened Again

A week later Revolutionary Spaces offered a program at the Old State House. All The Voices In The House: Hear My Plea and Know My Truth was both reenactment and reconsideration of the idea of a petition, a plea, an articulated hope for justice. Speakers spoke from the same balcony where Thomas Crafts read the Declaration of Independence to the people of Boston on July 18, 1776. Abigail Adams was there that day, 248 years ago was Abigail Adams. She described the experience to her husband, the future President John Adams, in a letter. “Great attention was given to every word,” she wrote.

Six years earlier, on March 5, 1770, the Boston Massacre had left five colonists dead, among them a Black man by the name of Crispus Attucks. A cobblestone medallion marks that spot today. I studied it as I listened.

Saxophonist Najee Janey initiated the program with a song that was mournful, blue, a sort of spiritual. The speakers–Amanda Shea, Anita D., and D. Ruff–read the original petitions and declaimed interpretative restatements that were part poetry, fully contemporary anguish.

The Petitions

Light gleamed from the gilded hides of the lions flanking that façade. Amanda Shea opened with the petition of Elizabeth Proctor in 1696. She had sought to recover the estate of her husband, John, executed for witchcraft in Salem in 1692. Her story sounded familiar.

My seventh great-grandad, Samuel Wardwell was hanged as a witch on September 22, 1692. His wife, Sarah, who brought substantial means to the marriage, was convicted in January 1693 although later reprieved. Their daughter Mercy was accused as well. Their wealth was confiscated and their young children left to fend for themselves. A son, Samuel Jr., sued the Massachusetts Bay Colony, eventually receiving inadequate compensation for their losses and suffering.

A petition from the Mashpee Nation in 1783 foreshadowed the horrors inflicted on the Osage Nation recounted in Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann. They demanded only that they and other Indigenous peoples be given the rights and privileges promised them by the leaders of the Revolution. I paused to think to the number of my ancestors who died battling Native peoples or in massacres initiated by tribal members.

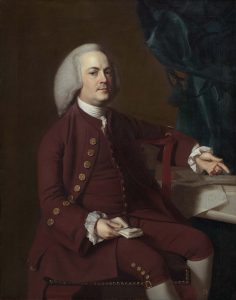

A passionate plea from Belinda Sutton in 1783, a woman of some seventy years, asked for a fair recompense for the work she had done for her entire life as a slave of one Isaac Royall. The owner’s name jogged my memory. Isaac Royall? Wait, isn’t he the subject of a famous portrait by John Singleton Copley in the collection of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts? I became familiar with that image fifty years ago. Belinda Sutton’s agonizing words, however, were never part of anything I was taught.

The Voices of History

We think of history as a set of discrete episodes in the past, events over and done with, whose dates and circumstances are regurgitated as a demonstration of our education. Nothing about this evening’s speeches felt over and done with.

Every petition was just. Each petitioner had suffered irreparable harm.

If the voices rang true to me, how much greater is the clarion call among people who have never benefitted from my privilege or enjoyed my blessings?