I read the new history of my school, Emma Willard School in Troy, New York and paid particular attention to the summary of my own era within those “grey walls protecting.” I am struck by the paradox of the book’s enveloping familiarity and its utter strangeness.

Was this the place I spent four crucial years of my life? Are those the people and events I remember? Is that the reality I share?

It would seem that a narrative that strives to be objective often contradicts the unique perspective of experience.

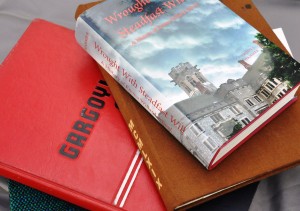

Let me say first that I think Trudy J. Hamner’s labor of loving scholarship is a remarkable accomplishment. She has provided 577 pages of exhaustively documented text that offers an unparalleled overview of the life of the founder, her goals as an educator, and the social, political and economic challenges faced by women from the beginning of the 19th century to the present. I found the book a real page-turner. I read my autographed copy—a gift from classmate Anja—in less than a month, something of an achievement given that it resided primarily on my bedside table.

I am struck most forcefully by the challenges to my memories—and please understand that I do not regard my memories as gospel. A repeated note in the book was the dubious scholarship of the student body during my era and in the classes preceding and following mine (I arrived in the fall of 1965 and graduated in 1969). My own experience was that I went from being a bright but—in truth—lackadaisical student who got very good grades primarily for acquiescent behavior to being a person of inconsequential accomplishments in a group of genuinely powerful minds and disciplined intellects.

The girls I met knew things I didn’t. They had read innumerable books I had never cracked and possessed a world view I could only envy. When told by my mother, who had canceled my interview at Dana Hall, that I would be going to Emma Willard I had asked, “What if I don’t get in?” It was a genuine concern for me. Before I arrived I was intimidated by the school’s reputation for rigor. My general sense of the school in 1965 was that it was a powerhouse, a place for young women whose goals included Nobel prizes, writers of the Great American Novel, and for all I could imagine, the White House. I was not that kind of girl. I was ordinary, adequate in most departments but inconsequential.

This book confirms for me that the abstractions of history do not necessarily convey experience. The narrative of principals and their administrations, the financial challenges they faced and social quagmires they negotiated is informative. It is also my experience that we students were oblivious to the questions of vision, administration and finances that preoccupied the leadership, faculty and trustees.

When I arrived as a freshman, my mother (Emma Willard class of 1943) left a special gift: a peck of Macintosh apples and a box of Hershey bars. She said there was no better way to make friends than to offer hospitality. She was right. Hardly had she left than Suzie L. knocked on my door and said that a group were watching television and had heard that I wanted to share my snacks. I loaded the skirt of her uniform—the gingham shirtwaist unie that came in crayon colors—with apples and chocolate bars and waved her on. No one else may remember that largesse—but I was so excited to offer it.

Then there were events that left us changed. Sophomore Paula Klein’s suicide in 1969 is summarized in a short paragraph; it remains a vividly detailed and lengthy narrative in my mind now, forty-four years later.

That Sunday morning a group of us were gathered in Sage living room at a “Housecoat Service” conducted by Bobbie Hutchinson. I was seated in an chintz-covered wingback when Principal Bill Dietel came in quietly, stopped and placed his hands on the back of my chair. Bobbie met his eyes and completed her remarks. She met Bill’s eyes again and he spoke, asking seniors to remain and underclassmen to head to the auditorium in Slocum Hall over ground. He was very specific about saying that students should not use the tunnel. Bill gathered us, the seniors, around him and said that he needed us is a way he had never needed us before, that we were to move through the dormitories, make sure all students went to the auditorium overground and he thanked us for help that we would be giving him. We did as instructed. He carefully and painfully explained that the school had suffered a terrible loss, all the more terrible because this student had taken her own life. Bill told us her name and I sat there stunned as most of my classmates and so many other students turned to each other and asked, “Who? Did you know her?”

I did know her. She was a friend of my “Little Sister” Weezie; she was the “Little Sister” of my good friend Donna and was a girl whose frailty had already caught my attention. Once, while passing in the Slocum-Sage tunnel, I smiled and said “Hi,” and she shrank in fear up against the wall. A few weeks later, I was eating lunch with Anja and a French teacher, Ms. Fish. Paula emerged from the kitchen carrying her tray and looked around the crowded dining room. She finally sat at our table, as far distant from any of the three of us as she could manage. The earlier episode still fresh in my mind, I smiled quickly at Paula and looked away so as not to put undue pressure on her, but still to indicate welcome. She sat. She ate. She left.

Later on that awful February day—after I had wept my own horror into relative containment and offered what support I could to the younger students—I accompanied Weezie to Slocum in search of phones we could use to contact our parents. We took the underground route and we paused as we came to the laundry room where Paula had brought her pain to an end. We went in, my arm around Weezie’s shoulders, so I could prove to her—and to myself—that there was nothing to see, nothing to fear. And there was, in truth, nothing to see. When we returned to that subterranean hall, Bill Dietel was standing there. He happened to have been walking the campus, watching, listening, being prepared to help. He opened his office and let us use his phone.

There is immeasurably more to my memory of these events and my four years in Troy than I recount here. There is more to my memories of the school as I knew it from September 1965 to June 1969—and my memories do justice to no one else, student, faculty, staff member or trustee, who was there at the same time.

Wrought With Steadfast Will: A History of Emma Willard School is a remarkable book. By focusing on the life, ideals and legacy of a remarkable woman born in the 18th century, Trudy Hamner enriches the story of the birth of the this country, the complex evolution of educational thinking in general, and the role of women in nation-building and nation-saving over the course of two hundred years. The story, however, requires the full chorus and no solo voice can do it justice.

Hello,

I just read your blog entry with interest. I have resisted buying ‘Steadfast Will’ thus far, given all the reports of how the 60s – 70s students and academics are portrayed (I’m class of ’74). Your excellent post leaves me on the edge, still. During the 70s, We had our share of runaways, troubled girls, and drug abusers, to be honest, but the academic rigor and the keen minds of my peers, and the intensity of our experience, are unquestionable. Somehow, paying $50 for a book that lacks sufficient insight into the incredible student talent and intellectualism of our era leaves me a bit cold…

: )

Terri, were you at the Reunion/bicentennial? That was an amazing weekend for me. As I hope my post made clear, the section of the book that deals with the later sixties and beyond struck me as thin and somewhat arbitrary. The first part, pretty much everything that goes up through WWI, is just excellent, though, and you might find it interesting. Anyway, I think it was extremely difficult for Trudy to write “living history.” Nearly all the key individuals are still alive; there are all kinds of sensibilities, not the least those of financial supporters, that must be managed. Having said that, the memories of my own classmates were so divergent and dissimilar that in our tsunami of emails during the spring and our conversations that May weekend we felt we had been in different schools–sometimes on different planets. (I collected those memories in a spreadsheet and they make startling reading.) Dennis Collins was your principal, correct? My experience of him–I was a class fundraiser–was pretty bad. But most of all, I agree with you: Emma students were simply some of the smartest, most creative and powerful minds I have EVER encountered, and if anything, my conviction about that has only strengthened. I hope your own experience was a positive one. Thank you some much for reading the post–and writing to me!