Matthew Adelberg turned twenty-one a few days past; when I look at the artist who once was a student in my art history classroom, I see something closer to the boy at his bar mitzvah. This exhibition at the Dadian Gallery at Wesley Theological Seminary in Washington DC is Adelberg’s first solo gallery exhibition, and quite the birthday celebration. I remember well—about a year ago—when he told me that it was in the works. The news came during his annus mirabilis (or maybe the miracle year-and-a-half) when his art was embraced by Victoria Wyeth (of the famed Wyeth family), when he received the “Novice Teacher Award” from The Louise D. and Morton J. Macks Center for Jewish Education in Baltimore, and most recently, a grant from the Elizabeth Greenshields Foundation. The exhibition’s opening was celebrated with a reception and talks by artist and curator.

This annus mirabilis included the horribilum eventus of a car accident that nearly took his life. A driver distracted by texting sideswiped Adelberg, sending him into the Jersey barrier. He showed up in my class looking like he belonged in nursing care. Yet this was also the year that he found his spiritual center, forged a “personal relationship” with his “higher power.” In fact, Adelberg’s life and art both encode paradox; they are narratives replete with contrasts and contradictions, rich with irony.

Let me return, however, to this exhibition. “Matthew Adelberg: Lineage” addresses the ideas of spirituality, identity, legacy, self-determination. It speaks to biography but goes beyond personal narrative to the inexplicable forces that shape us and our destinies. The exhibition is excellently organized by Trudi Ludwig Johnson, curator of the Dadian Gallery and member of the academic advising team at the Maryland Institute College of Art. Many of the works chosen engage with Judeo-Christian iconography and genres: narratives of saints and Jewish history. Others are symbolic still-life and self-portraits. Through these structures, the artist grapples with the demons of abuse and abandonment, and grasps the light of love and determination.

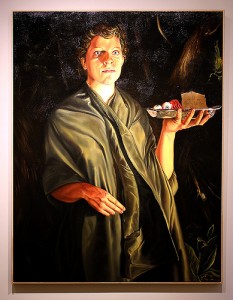

Saint Lucy represents the story of the blinded fourth-century martyr. She is shown here, as in so much traditional art, with her eyes on a salver. The work alludes to the Saint Lucy by Francisco de Zubarán (1598-1664). As in the work of Adelberg’s artistic idol Caravaggio (c.1571-1610), though, the figure fills the shallow stage of the picture space, reaching into the viewer’s space and psyche with her gesture and her gaze.

Adelberg spoke about this image as a meditation on his mother, her strength as an abused woman and a single parent, and as he did, other thoughts ran through my mind. As I listened to him, I also heard the lyrics of Cat Stevens’ Moonshadow: “…if I ever lose my eyes, / if my colors all run dry…” Vision is the artist’s greatest strength; what is visible is the measure of his accomplishment. Saint Lucy suffered because of her faith, but her faith was also the source of her redemption. Adelberg, self-described as a “bad kid,” turned to art when an injury sidelined him on the lacrosse field. In doing so he turned away from the physical aggression that belonged to his abusive father and embraced the indestructible love that he knew from his mother.

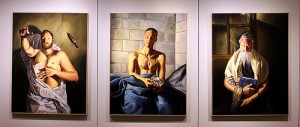

The Lineage Triptych inspired by the Talmudic story of Resh Lakish and Rabbi Yochanan, the man of violence and the man of scholarship, was extremely moving. The hirsute and muscular form of the gladiator and the introspective figure of the old teacher bracket the artist’s self-portrait. The rabbi persuades the gladiator to abandon violence for cerebration. Eventually, the two compete over an intellectual question, the correct choice of knife to use in the ritual sacrifice of animals. The student’s argument prevails; the teacher, like some aging fighter, lashes out in the face of defeat. The emotional wound sustained by the reformed gladiator proves physically fatal. The rabbi realizes that his intellectual violence was no less lethal than the gladiator’s sword—and rationality dissolves into madness.

The story as Adelberg presents it is a parable of the power of mind over body but also a story of the fragility of belief systems. The format of the triptych in its most traditional sense speaks of the altarpiece; the iconography suggests a sort of “divinity with saints.” The artist occupies the center panel, the “divinity panel,” and is flanked by the gladiator and the rabbi. The artist holds sway over brutality and spirituality even as he is the child of that duality. Adelberg identified Barry Nemett as the model for the rabbi, earning a laugh when he said that Nemett is the chairman of the painting department at MICA and a teacher. It is perhaps a coincidence that Nemett is a sage-looking graybeard; it is not a coincidence that Matt recognized his Rabbi in his rabbi.

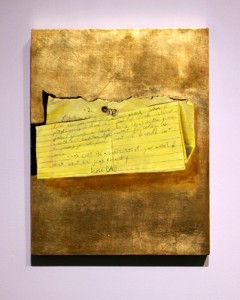

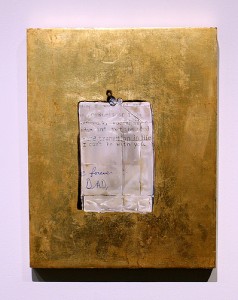

The works that speak to me most directly are the small “icon panels,” the trompe l’oeil representations of letters written by the artist’s father, push-pinned to a surface of gold. These letters are presented like fragments of some ancient manuscripts, pieces of paper unfolded and refolded countless times. The writing is legible—precisely duplicating the irregular taps of an old typewriter or careless scrawl on yellow tablet paper—but phrases are isolated, stripped of meaning by the folds that demarcate them.

An icon, according to The Thames and Hudson Dictionary of Art Terms, is a “painting by a Greek or Russian Orthodox believer on panel, generally of a religious subject strictly prescribed by tradition, and using an equally strictly prescribed pattern of representation.” Backgrounds are frequently gold, the color representing both light (symbol of the sacred and the realm of heaven) and the idea of the highest value, of absolute worth. In one sense the letters are worthless. In reality they are unwanted artifacts acts of violence, relics of man who failed utterly in his humanity. These scraps, however, are preserved with lapidary significance, endowed with the mystery that shrouds equally the decoding of language and human emotion.

In answer to a question about beauty, Adelberg said, “for me something is beautiful when it is true, when it is genuine.” The narrative that inspired this work is tragic; it is hard to see it as beautiful. Adelberg’s art sometimes occupies that space where “genuine” and “literal” converge. He describes his art as a way to work out the issues that consume him and he is a young enough man to not always recognize how his specific issues are but manifestations of human questions and universal verities.

That is as it should be.

Matthew Adelberg is a Jewish artist whose imagery is often limned through Christian iconography. It is easy to see the attraction of his art to an organization (the Henry Luce III Center for Arts and Religion at Wesley Theological Seminary) dedicated to “exploring the intersection of the arts and theology.” Matt seems to reach directly to the glory days of Catholic art, using color and light to make manifest the matters of the spirit that have always transcended any religious dogma. As a realist painter, he readily connects with viewers’ desire to see in art a mirror of their lives and beliefs. As a modernist, he makes his painting a conversation with the artists who precede him, inspire him, challenge him. In March 2013 I wrote about him in this blog (“The Painter and Modern Art“) and closed with these words: “Matt walks the secure ground of his own truth now. That has given him a good start down the rocky and challenging trail of truths we all share.”

I can see that he has been hiking hard and fast.