I think the studio teacher said something like “What is that supposed to be?” during a painting critique.

The comment is a variation on an old, old theme in since “Modernism” earned its capital M: “whatever you are doing, it clearly doesn’t meet the standards of ‘good art’.”

The Impressionists earned their name from hostile reviews that said “Bah! They are nothing but impressions” and describing works as “palette-scrapings.”

Rodin responded to criticisms of the design commissioned for the city of Calais, France, the magisterial Burghers of Calais, saying “I read again the criticisms I had heard before but which would emasculate my work [and] submitting to the law of the Academic School… I am the antagonist in Paris of the affected academic style… You are asking me to follow the people whose art I despise…”

No less singular a member of the avant-garde as Henri Matisse was bemused by the paintings Georges Braque exhibited in 1908, grumbling about Braque’s “petits cubes” and inadvertently coining the term “cubism.”

Pejoratives have long made the most lasting descriptions in art history. Renaissance writers maligned the barbaric features of the “Gothic” period. Eighteenth-century Neo-Classicists denigrated the excesses of the “Baroque.” Modern artists tried to change that. In the twentieth century, artists from the Italian Futurists to the Dadas chose their own monikers. In 1950, Willem deKooning said, during a symposium attempting to analyze the goals and ideals of the new American art, It is disastrous to name ourselves. DeKooning and his peers got stuck with “Abstract Expressionists” anyway.

Art history has established that “good” art, in twentieth- and twenty-first-century terms, is “Modern” art. That means it is original, experimental, edgy, disruptive, and frequently unintelligible to all but a small group of intellectuals and dealers who make their livings parsing it and selling it. Now the great pejorative is Rodin’s “Academic.”

Which brings me back to Matt Adelberg, whose work so challenged his instructor.

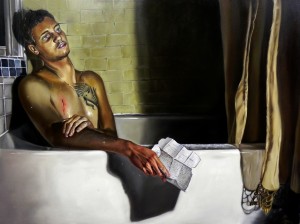

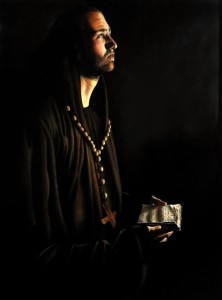

Matt is a painter, a real painter, the kind who thinks about color and light and space and how brush, palette knife, rag and other implements can cover a flat surface with paint in order to invoke form that carries meeting. He has a passion for the Old Masters: when I met him, nearly the first thing he said to me was that he was crazy for Caravaggio and that he had just read the 2010 biography by Andrew Graham-Dixon, a book I was part-way through. He demonstrated great appreciation for the artists we explored in Renaissance to 1855. He’s perceptibly less enthused in my Modernism and Beyond, but has found artists that pique his interest.

As an art historian I’m delighted that he wants to look at “old stuff.” As a gray-haired geezer, I love that there are young people enraptured by the idea of painting, the problems of representation, and the possibilities of expression.

He is in his hommage phase of growth. He is inspired by Caravaggio, of course, but also by Francisco Zurbarán and Jacques-Louis David. Matt is filled with the passions and anxieties of the young; his emotions and aspirations are at the center of his universe and he has begun the thesaurus that will give him the wherewithal he needs to merge his universe with the cosmos, to find in the personal a metaphor for the universal.

In this day and age, it is hard to grasp even the idea of art. Painting and sculpture have moved over to make room for video, digital mediums, and performance. The possibility of the lasting and archival has made way for the ephemeral and its attendant documentation. Concept is elevated and execution is often given short-shrift. Grandiose ambition is applauded even when it is mainly grandiosity.

And “Beauty”? The closing lines John Keats wrote in his Ode on a Grecian Urn are often all we remember of the poem, but perhaps there is a reason for that.

When old age shall this generation waste,

Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe

Than ours, a friend to man, to whom thou say’st,

“Beauty is truth, truth beauty,” – that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.

Truth and beauty cannot really be severed, at least not in my mind. Truth is not an absolute, something that can be quantified or framed in language suitable for FaceBook likes or bumper sticker proselytizing. Beauty is not a condition of prettiness, a quality of optical seduction. Truth can be harsh and beauty can be searing.

Matt walks the secure ground of his own truth now. That has given him a good start down the rocky and challenging trail of truths we all share.

It is good, if artists look at their predecessors, as the author states. Yet, while Hieronymus Bosch could rely on the knowledge of history and symbols of the time, today’s painters / artists cannot. The context of imagination (making images) now more and more is build upon the www. Thus, using symbols will meet a blank face. Perhaps imagination must strike the veins beneath the surface, and not just reflect “truth”. After all, truth is a description of geography: True brightness must be sought at the Sea at Ponte d’Allure.

Says drager meurtant

Drager Meurtant: Thank you for your comment and compliment. You are right that artists like Bosch had the benefit of a culture widely familiar with specific symbols and a strong sense of their own history. Those symbols took on such richness and complexity, also, as artists used and reused them, often making references to famed works of the past. In this “post-modern” world, art seems often to be “about art” but the ideas of the artists are sort of “inside jokes,” concepts and references that most people neither recognize nor understand.”In a more homogenous society, one that shares a particular ethos and religious outlook, art–or at least public art experienced in churches, government buildings and popular celebrations–was a truly shared experience. I like your point about imagination and the wwww; one might think that the wwww would provide a shared experience but I think it just contributes to misunderstandings. One thing I like so very much about this young artist is his interest in learning that ancient, common language and and using it today to make himself understood.

I found your work by searching for “Pont d’Allure.” That is a lovely piece, in fact quite moving.

When experiencing art, best at close distance to the actual art work, I’m most attentive to the area slightly below the diaphragm: that’s the area most sensitive to a message (quality?)

ART is a being, essential to humanity. But there are times, in which it is neglected, in particular, and right now, by the waves of images from www. These may dull perception. But I trust, in the end, that senses will be touched and moved by mere quality and meaning.

More movement: “meurtant building on the move”

To all: keep going

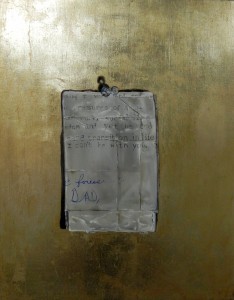

Thank you for continuing the conversation. This young artist has his first solo show in Washington DC Jan 20-Mar 7. That will give everyone a chance to get close and genuinely experience the beauty of the painting and the idea. I constantly remind my students that what we look at in the darkened classroom is not the art–it is just a faint simulacrum.

Thank you, for enlightening a young artist that – from what I can see here – does not carry a personal portfolio of exhibits and positive art reviews weighing 2 lb. Please let me know what the perception/reception will be of his solo show. And advise Matt not to get framed (http://www.flickr.com/photos/97577184@N04/10552109516/).

Wow, hi it is really nice to meet you. I really love your art work and it’s more realistic, 100 times more realistic than mine. I have been drawing since I was about 2 years old, now I am 12, but I wanna end up being a dramatically great artist like you. If it is okay I would like to send you some of my pictures if I can. You are such a great and perfect artist. Please if you can answer my message, I would like that, have a good day.

Samara, I am so glad you wrote. You are only 12? You seem to be much more grown-up than I would expect.

I wrote this blog post, but the artist, Matt Adelberg, has a website: http://matthewadelberg.com/. You can see more of his art there and there is an email address if you want to contact him.

I agree with you, Matt is a great artist. He is devoted to his craft and works very hard at constantly improving his skills. His ideas, his feelings about the world, are also at the center of his art. That makes his painting more than just wonderful examples of painting skills. Anyone, I think, can be skillful; it takes a great artist to say important things.

I wrote another piece about his art when he had a show in Washington, DC. The link to that post is: https://ellenbcutler.com/2014/01/29/matthew-adelberg-lineage/.

You have a good day, too, Samara. Keep making art. Very best wishes to you. Ellen