In the course of making some point or other, I asked the high-school age students in my summer workshop what their favorite books were. Any book, I said, it could even be a picture book you read with your parents. Not one of the eight mentioned a book. Finally, a lad allowed as how a grandparent had given him a book of poetry which he had read, enjoyed and kept.

These students were all American save one and all young people I would describe as privileged, born to parents who value education.

I should be beyond shock now, but I confess I am not.

To not have a cherished book is like saying one does not have a favorite food or that there is no music you tune in when on a road trip. How can the word “book” not conjure a magical immersion in some different universe uniquely parallel to the one inside one’s soul?

Out of the eight, not one, I think, would have chosen “reading” if given a choice of activities from the following list that deliberately excludes “cell phone”:

- Reading a book

- Baking cookies

- Going shopping

- Playing a sport

- Watching television

Could any of them imagine reading a book so often and so thoroughly that it becomes committed to memory and hence to posterity, like the books, words really, saved in Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451? Apparently not.

Yet I have spent much of my life in search of books whose titles and authors have long since gone lost in the junk heap of my memory. I spent years trying to recall Ruth Sawyer’s The Enchanted Schoolhouse read aloud to our class in 1962 by our fifth-grade teacher, Della Zelda Schneiderman. I spent even longer than that trying to pin down a book that I found, oh around 1960, on a shelf in our summer place on Squam Lake in New Hampshire. I had read it over and over across many vacations and remembered the illustrations vividly. When I described it as a narrative about a sister and brother, sleds and colorful tassels, a snowstorm and a tree that provided shelter, I was met by blank stares, shaking heads.

This past March, I read a short piece in The New York Times about a blog called “Stump the Bookseller.” For a token fee, about four dollars, this crowd-sourced service provides access to an infinitely deep crowd of people who seem to know everything about every children’s or young-adult book ever written. As I scanned through the queries, I fell over titles I hadn’t thought about in fifty years or more. I immediately drafted my description:

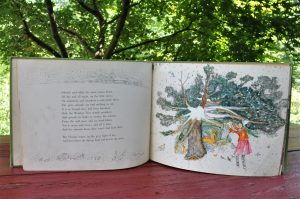

It is a picture book. The illustrations are similar to pen-and-ink drawings that have been colored in, quite bright, beautiful sense of line.

The story is about a girl (and her brother) in a northern country (Scandinavia?). In the winter (Christmas?) they decorate sleds with strings of colored tassels for some procession. The girl cleans house for an old woman who makes her the tassel string. The girl gets caught in a terrible snowstorm on the way home and takes shelter in the root-hole of a much loved ancient oak tree. (The oak tree is a character in the story too.) This is where she is found.

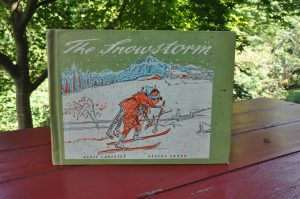

Within two days and despite my errors–it was Switzerland and not Scandinavia, the Weather Tree was a pine not an oak–I had two responses, both, needless to say, correct. The story is The Snowstorm written by Selina Chönz and illustrated by Alois Carigiet. Originally appearing in German as Der grosse Schnee in 1955, it was published in the United States by Henry Z. Walck, Inc. in 1958.

The copy I ordered from AbeBooks.com is in a library binding, in good shape but a little dirty, showing traces of pencil scribbles and splatters of watercolor paint or something. It was stamped in front, “Paradise Elementary School Library.” On the title page it was stamped “Hillcrest Elem.” There is a Paradise Elementary School in Paradise, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, about an hour from my home. There is another school with the same name in adjoining York County. Maybe there are others. There are Hillcrest Elementary Schools in Catonsville, Maryland; Frederick, Maryland; Southampton, Pennsylvania; and Drexel Hill, Pennsylvania. And Los Angeles, California, and probably a dozen other communities across the country.

I sat down to read, quietly saying aloud the rhyming, metered lines.

On the copyright page, a large black stamp: “DISCARDED.” The same stamp mars the illustration of Ursli following the tasseled string in the storm, desperately looking for his sister Florina. A third stamp appears on the last page, as though a comment on the text:

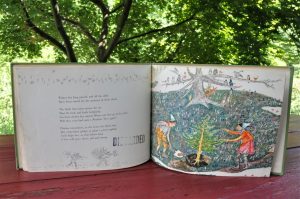

Winter has long passed, and all the sleds

Have been stored for the summer in their sheds.

The birds that come across the sea

Must fly back and forth helplessly,

For their shelter lies ruined. Where can they go in the rain?

Will they ever find such a Weather tree again?

Florina remembers, as she hears the birds sing,

Her wintertime pledge to plant a green sapling.

Ursli helps her, so that before long

A tree will grow there, tall and strong.

DISCARDED.

This lovely story about independent children and the nature all around them was discarded for being too old, insufficiently entertaining in contemporary terms, perhaps lacking in multiculturalism, possibly irrelevant.

When I loved this book as a child, I couldn’t imagine a world like the one I live in now.

A president would never brag about assaulting women or mock a person with a disability or humiliate the country as a whole in the eyes of friends and foes alike around the globe. Bullies were in good supply, but bullies were mainly children and racists like the white people I saw screaming at Ruby Bridges and James Meredith has they arrived at school and university as the first African-Americans to attend classes. Based on the conversations at our dinner table and headlines in the newspapers, I understood that my country was imperfect, but I also knew that it was a work in progress and a society that was good at heart.

What I feel now is that everything is being…

DISCARDED.