I’ve got an old mule and her name is Sal

Fifteen years on the Erie Canal

She’s a good old worker and a good old pal

Fifteen years on the Erie Canal

…

Low bridge, everybody down

Low bridge cause we’re coming to a town

And you’ll always know your neighbor

And you’ll always know your pal

If you’ve ever navigated on the Erie Canal.

That was a popular ditty in my elementary school, back in the late fifties or early sixties. Thomas S. Allen wrote the words in 1905, some 80 years after the Erie Canal opened to traffic. By then real mule power had been all but replaced by mechanical horse power. The Erie Canal itself, in fact, had almost been replaced by the New York State Barge Canal System, waterways designed for self-propelled vessels. Whole sections of the original, along with the villages and businesses that thrived there, drained away and disappeared.

2017 marks the 200th anniversary of the start of construction (2025 will celebrate completion) so when my Dear One and I felt in the mood for a little road trip before anything clogged up an open week in the calendar, off we went. We ambled through Scranton, Pennsylvania, and Corning, New York, and started our tour in Syracuse at the Canal’s halfway point

The Erie Canal Museum housed in the 1850 Weighlock Building provided the facts and context.

In the first few years of the 20th century, our parking space on Erie Boulevard would have been in the canal itself. All boats would have floated into the weighlock and been assessed on the cargo carried.

When the Erie Canal was rerouted north to Oneida Lake, much of the southern loop that brought it down to Syracuse was filled in. Exploring the eastern half of the canal is largely a matter of moving from park to park, from one archaeological dig to the next. Bits and pieces remain. Small museums like the Chittenango Landing Canal Boat Museum can only suggest the immense and ongoing effort it took not just to maintain the waterway but to build boats and keep them in repair.

As with any trip, this one was a chance to get to a few more museums on my bucket list, and with the museums came thoughts about how the Erie Canal shaped economies across a big piece of real estate. Consider the often worn and degraded but gorgeous architecture in towns like Syracuse, Rome and Utica. It is apparent that the last seventy-five years to so have not been kind. One hundred years ago and more, coal, grain, lumber, all kinds of raw materials and manufactured goods traveled from the seaport of New York City up the Hudson and westward from Albany all the way to Buffalo, from where shipments continued west through the linked Great Lakes. Trade routes for salt from Syracuse, copper metal and objects from Rome, textiles and furniture from Utica brought wealth and educational and cultural institutions to the area.

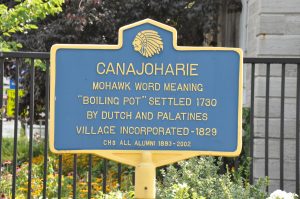

The Erie Canal also opened up the West and transferred even more Indian lands to white settlers. Monuments, like the one just outside the Arkell Museum in Canajoharie, celebrate the courage of colonial and early American military who fought and vanquished the Native Peoples from whom they essentially stole what is now the United States of America. A treaty signed by King George III establishing boundary lines that protected Indian lands from encroachment by English settlers was renegotiated repeatedly, each time pushing Native Peoples farther and farther from their ancestral lands. Our stop at Fort Stannix in Rome, a U.S. National Park Service monument, left me feeling discomfited—and it was not just because their didactics needed a proofreader. They made a conscious effort to make Native Peoples a part of the narrative—and succeeded only in demonstrating that Native Peoples were systematically erased from our national narrative.

Right now, in August 2017, we are having arguments and fighting battles over the meaning of monuments. Baltimore removed four Confederate monuments overnight; a statue of Chief Justice Roger Taney, author of the Dred Scott decision, was taken down in Annapolis. Protestors in Durham, North Carolina, pulled down the Confederate Soldiers Monument. Walls went up around the Confederate monument in Birmingham, Alabama.

The Erie Canal was an extraordinary feat of will, strength and pig-headed determination. The energy that fed that determination, however, was fed by the expectation of rewards, of the acquisition of land, the accumulation of wealth. In our history, this was always a story of winners and losers.

The Erie Canal was a winning proposition for Governor Dewitt Clinton of New York, for his allies and those who saw the project through completion and subsequently through expansion.

It was also the ultimate loss for the Native Peoples, the Five Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy.

I need to think about the history we claim as the winners and think about how to make that narrative more truthful and complete.