At the time I was about halfway through this wonderful book, my Dear One and I were watching an episode of Homeland, a political thriller starring Mandy Patinkin and Clare Danes. I’ll admit it—it’s the seventh season and we’re into it.

At that particular moment (the Russians are the current bad guys which seems very topical), a French woman Simone Martin, who may or may not be working for the Russians, and who may or may not be an assassin’s target, is in a sort of safe house isolated in the woods somewhere within driving distance of Washington DC. There is a wide lens shot through the living room into a bedroom where Simone lounges on a bed reading a book. A noise. Sudden action. Simone sits up, closes her book and sets it on the bed.

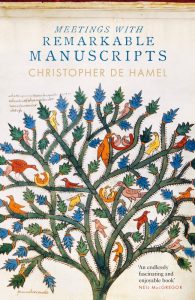

The jacket identifies the book as “Meetings.” Easily seen is the crown of a tree filled with birds and nests, a detail from the “Dream of Nebuchadnezzar,” an illumination in the Beatus of Liebana’s Commentary on the Apocalypse. The narrative comes from the Old Testament Book of Daniel. I squeaked, “She’s reading my book!” I sent an email to the author to see if he knew of this cameo appearance. He did. An intern at the Getty Museum saw the clip, told the curator of manuscripts who told De Hamel.

On the one hand, this is a triumph of cover design. The book appearing in such a context intimates its accessibility and perhaps even alter egos as mystery and travelogue. Meetings With Remarkable Manuscripts: Twelve Journeys into the Medieval World (Penguin Press, 2013) is a compilation of “interviews” with twelve manuscripts created between the late 6th and early 16th centuries. The final manuscript explored, the Spinola Hours, was made after Gutenberg’s invention of movable type in 1450. The “twelve journeys” explore eleven genres including two books of hours. Each manuscript, moreover, lives in a different archive: in Cambridge England; Florence, Italy; Dublin, Ireland; Leiden, Holland; New York City; Oxford, England; Copenhagen, Denmark; Munich, Germany; Paris, France; Aberystwyth,Wales; St. Petersburg, Russia; and Los Angeles, California.

As I read, I thought, “Ooh, this one is the best and most interesting manuscript, no, this other is actually more compelling, no, no, no, this is the one with the best back story!” My copy is now all a-flutter with yellow Post-It notes on which I have noted my ideas, my discoveries, my complaints. In these “Meetings” there has been much conversation and debate, a wonderful experience. The Wolfson History Prize, awarded for excellence in accessible and scholarly history, was awarded to Christopher de Hamel in 2017 and rightly so.

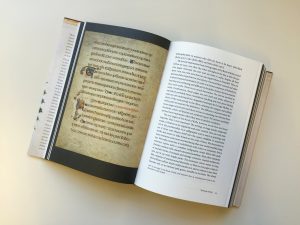

“A text page of the Book of Kells, with Matthew 18:19-24, including lions’ heads in the decoration of the initials”

De Hamel identifies these glorious books as “medieval.” Their dates and subjects, however, braid intricate connections between the death throes of the Roman Empire and emergence of an international Catholic Church at one end and the onslaught of the Protestant Reformation that lurched Europe into the modern era at the other. De Hamel’s style is informal and personal—although it is unfortunate that he tends to forget he’s not so much chatting with scholar-peers over a pint in a pub as he is introducing less erudite companions to beloved friends. I kept a dictionary at hand and once or twice resorted to the internet. The author apparently assumes the reader has an equally muscular vocabulary and a comparable familiarity with geography and history.

Technical information, however, is not always well explicated. I understood the process behind “collation” (how the pages were assembled into the binding). The alphanumeric code used to represent that organization and identify missing leaves, however, remains unintelligible to me. There are a few errata that ought to have been picked up during the copyediting and proofreading stages as well.

Each manuscript has a unique life story but similar questions are posed to them all. One query focuses on provenance, the list of owners that goes back sequentially to the original purchase. Related to provenance is collation, a determination of whether the pages contained within the binding are in the order originally intended and whether any pages are missing. There is also the matter of attribution: who were the scribes and illuminators and where was the workshop.

The explosive growth in printed books by the later 15th century, which drove increases in literacy, expansion of Protestant ideas and discoveries in science, also affected the production and collection of illuminated manuscripts. Such books, which had long been regarded as treasures as well as instructional materials, became even more desirable. Patrons commissioned ever more lavish volumes; collectors assembled enormous libraries. Book sellers and dealers manipulated markets.

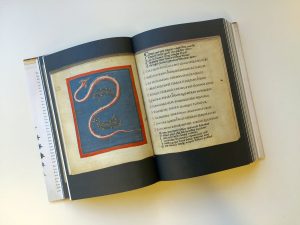

“Specimen double openings of the Aratea, showing Arcturus Major and Arcturus Minor, little bears rolling between the coils of a snake, marking the north pole”

Every chapter includes description of local landscape, the various libraries and repositories, and the charm or lack thereof of employees and the “invigilators” assigned to keep an eye on those who have gained entry and would study such books. There are countless coincidences that link these manuscripts. De Hamel delights in these connections, speculates on their meaning and the facts they bring forward or obscure. His knack for simply telling stories—and yes, maybe you want that pint while he holds forth—is exceptional. It is often in these stories that the magic of the books entraps us most. Here is an anecdote from chapter four, “The Leiden Aratea:”

One of the consequences of examining the original of a very famous manuscript is that the word rapidly flies around the library that the iconic object is out, like a rare bird spotted by an ornithologist on a social network. In the early afternoon, a group of Leiden Ph.D. students materialized in the reading-room and deferentially asked whether they might stand behind my chair while I continued to turn the pages. I found myself giving an unofficial tutorial…”