Honestly, qualified medical professionals and the Fresenius Medical Care/NxStage Medical, Inc. have extraordinary faith that someone like me is not going to precipitate a medical crisis.

I’m a full partner in this home hemo thing. I received six weeks of training—about eighty-four hours in all. Our Angel Arlene, the nurse who heads up our team, is a text or phone conversation away most weekdays; a tech from NxStage is on call 24/7. Even so.

I mean, I studied art history in college and graduate school. I’ve worked in museums and taught in the classroom. I’m quite good at talking and writing about art. Providing medical care and handling needles?

I would not have been attracted by my resumé if I were looking to hire a home-hemo partner.

So Much Can Go Wrong

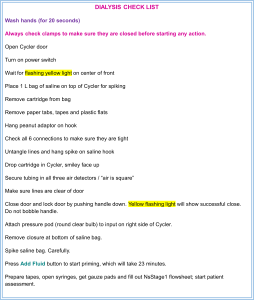

Now I have a step-by-step checklist I follow every single time. Just setting up the Cycler takes over three pages. Instructions for everything that follows—plus tasks like drawing bloodwork or giving medications—expands the checklist to seven pages.

Take the Cycler-Who-Must-Be-Obeyed. It brings everything to a screeching halt if you do anything out of sequence. There is no option but to stop, clear away the cartridge, toss the bag of saline, and start the twenty-four-minute process all over again. As happened this morning when I failed to press the “stop” button in the “snap, tap and stop” sequence.

The Pureflow machine makes the dialysate and drains the waste cleaned from the blood as it is treated. One batch is good for two treatments, then the remainder is drained and a new batch is started the night before the next dialysis. About two times out of five, something goes wrong and an alarm goes off. Usually an A33. Don’t really understand why it does that but the problem requires clamping off a pair of tubes, then pressing red for stop, green for go. When “Load Test” appears on the screen, I remove the clamps and hope for the best.

Alarms

So many alarms.

If the fluid sensor on the Cycler detects something wet, it beeps fit to wake the dead. If there has been a power outage, the Pureflow makes an insistent noise.

During treatment, the Cycler is talky and occasionally hysterical. Yellow cautions generally indicate that routine tests are underway. These alerts aren’t worrisome, just mildly annoying like a coworker in an open office with behavioral tics. Red alarms signal genuine problems, most often in the lines headed out (the arterial flow) or headed back to the patient (the venous flow). A 10 or an 11 in most cases, caused by weight from my Dear One’s arm on the tubing. Rearranging things, pressing red for stop and green for go, gets things back on track. Usually.

Every now and again, a red 24 appears and won’t go away, forcing a call for help. Sometimes our Angel Arlene can calm my agitation and walk me through the fix. Or decide when a premature finish of the treatment is required, what is called an “emergency rinseback.”

There is a laundry list of bigger, scarier issues. Trying not to think about those.

Maintenance

Then there is the maintenance.

The Pureflow PAK is the large and extremely heavy black box that is the brains of that operation. When it falls over on your leg and scrapes your ankle, the pain is considerable. The PAK’s life span is approximately three months and it warns you when it is about to croak. Or refuse to make a new batch of dialysate.

The waste line—the “pee line” as I think of it—collects the used fluids and returns them to the drain in the bathroom across the hall. Dialysate is sticky and mixed with blood byproducts, it can clog up the tubing. And it creates an unpleasant scent around the sink. The manual says clean it with a 10% bleach solution monthly. Angel Arlene says every two weeks is better. I’ve taken to doing it weekly. At the same time I pour a slug of bleach down the sink to kill odors.

The Cycler has a blood sensor that detects random bits of hemoglobin that leak out. Until the Cycler gave me a red 61 alarm during an initial priming. I am supposed to clean the sensor at least once a month. I checked the manual. Oops. I cleaned it for the first time six months into home hemo. Guess that needs a weekly schedule, too.

How Can I Screw Up, Let Me Count the Ways

The worst? The worst is doing something that either causes genuine pain or results in a mess.

Placing needles—cannulation—can be almost unnoticeable or it can be a serious owie. The worst part is that there is no useful way to tell when the needle is set to go in smoothly and without distress or when it is going to hurt. How much blood spurts isn’t an indicator of pain—but the patient gasping is.

Then there is a failing to staunch the bleeding at the needle site. The venous needle isn’t a problem. The flow heads back into the body there. It’s the arterial site that produces enough gore for a slasher film. Six minutes of pressure is supposed to prevent that—but sometimes it just doesn’t and suddenly the padding and tapes are saturated and blood is dripping everywhere. We have a “belts-and-suspenders” arrangement in place now. First, a full six minutes (or more) of pressure and careful bandaging of the site. Next, a wrapping with one of the bright-colored compression bandages left over from other medical procedures.

Partners, Indeed

All those “irrelevant” subjects I studied from kindergarten onwards, and all those non-career-track jobs I’ve worked over the years? Damned helpful as it turns out.

Every set of partners allocates the jobs differently, but here I am nurse, IT specialist, engineer, inventory clerk, pack mule and janitor. But the errors are all mine.