The headline of The Scranton Times on December 9, 1914 read THIRTEEN MINERS KILLED, Dropped Dynamite Blows Bottom Out of Cage.

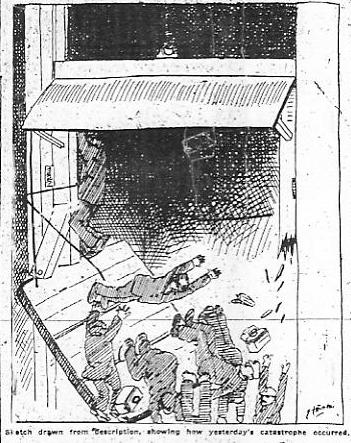

The Diamond Mine Disaster, 9 December 1914, Scranton PA. “Sketch drawn from description showing how yesterday’s catastrophe occurred.”

Actually there was no dynamite. The elevator that carried miners up and down the Tripp Shaft at the Diamond Mine had a rotten floor. Regulations, moreover, allowed only ten passengers and there were thirteen on board that day. The bodies retrieved were so mutilated by the fall that it took a while to identify them all.

One of the men who died that day was my Dear One’s grandfather Casimir, a 34-year-old immigrant from Lithuania and the father of three small children. Another was his grand-uncle Petras, age 24.

The oldest victim was 60-year-old Thomas Thomas, the elevator operator. After a lifetime spent in the mines he was frail and shuffled onto the elevator with difficulty. The only man who survived, Martin Bolinski, was so terrified of the conveyance that he habitually clung to the side of the car. His paranoia saved his life and he dangled from the wall of the carriage until rescuers could pull him to safety.

The bosses argued that the miners—mainly impoverished immigrants from Eastern Europe—carried dynamite with them, strictly contrary to the rules. The dead, they said, were the architects of their own destruction. Evidence, however, shows that the floorboards were rotten. The carriage snagged three times and the jerks as it resumed movement put deadly stress on the floor. The result was that Casimir and Petras and four others were carried in their coffins into St. Joseph’s Lithuanian Church and seven fellow miners were mourned elsewhere.

The inquest continued for weeks, with multiple delays. As articles moved from the front page of The Scranton Times to less prominent locations, they became merely notes about postponements. Feeling the need to get back on the road, we stopped reading. As far as we know, there were ultimately no reparations, no insurance payments, and no apologies. Certainly no blame adhered to those Teflon bosses, those wealthy men who ran the railroads and owned the coal mines.

Scranton these days is like some venerable, great tree, magnificent at a distance but hollow at the core. There are handsome buildings, gorgeous examples of 19th century revival styles and fine early skyscrapers with neoclassical ornament. The Gothic Revival Albright Library, where we scrolled through microfilm and paged through books and files, is a wondrous place with its stained-glass windows, mosaic floors and carvings in wood and stone.

Yet the passage of time has not been kind. The Electric Building with is self-confident display lights is worn and half-occupied. A group of Asian people holding maps and looking curious crossed over to the park where I was taking photographs. Tourists? Looking perhaps for Dunder-Mifflin and the cast of misfits that sell paper products from that anonymous Office in television’s imagining of Scranton? Storefronts are empty, streets seem to have plenty of parking spaces available, and pedestrians are few. In North Scranton, where my Dear One was born and his family chattered in Lithuanian, the enormous and imposing Junior High is boarded up and derelict and the lace factory where his mother worked is idle. The location of the Tripp Shaft of the Diamond Mine, where those thirteen died in 1914, is a shopping center; an adjacent area of dirt and rock, the tailings from the mine, are all that remains of what brought so much wealth to owners, so much hardship to workers. Houses speak not of working-class struggle but of entrenched poverty. The house on Theodore Street where he lived as a small child and where we would visit his Aunt Mary is abandoned. Someone cuts back the weeds in the front but the backyard is thigh-deep in growth.

We dined with cousins in nearby Jessup, a town of houses set close together, a neighborhood that reminded my of my childhood in Cleveland Heights, Ohio. It was a fine home-cooked meal of pasta and mozzarella salad and cake. Happy beagles begged for attention and teenaged girls sparkled. We shared family notes and filled out genealogical blanks. It was a truly American Scene: Lithuanian cousins, a half-Italian daughter, granddaughters whose father is of English, Polish and German extraction. There were emotional memories of Grandmother Anna’s chickens, plum trees and the circular bed of flowers at the house on Stanton Street.

On our way out we drove by the old homestead. The house is for sale. The fruit trees and chicken coop are long gone. The nearby corner where my Dear One dug worms with Grandmother’s second husband, also a miner named Casimir, is now shaded by pine trees.

Sometimes the more things change, the more the world becomes a different place.

I have been researching my husbands family an came across your website. I believe the Martin Bolinski mentioned is my husbands great grandfather. I know he was from that area and the census records listed his occupation as a coal miner. Would love any newspaper clips you may have found.

Brynn, that is fascinating. I need to dig out the files, see what we photocopied. There is at least one good article that provides some details. The folks at the library in Scranton were extremely helpful. If you cannot get there yourself, you might be able to get them to help you out for a fee. It is a fascinating question: how many descendents are there of the men caught up in the Diamond Mine Disaster?