Art Nouveau is not really my thing—too ornate, too feminine, too precious. I admire certain artists and objects and connect to the focus on materials and their unique qualities, but l would not want an Art Nouveau home or Art Nouveau furnishings, or even much in the way of Art Nouveau jewelry. I understand—and teach—that Art Nouveau, British and American Arts & Crafts, Spanish arte moderne, German Jugendstijl and Austrian Sezession are all manifestations of a shared inventiveness at the fin-de-siecle. But I don’t think that I fully bought into my own assertions.

Brussels, however, has made me aware of my blinders, brought me to understand that my judgments come more from ignorance about the architects, artists and artisans who created within the style than any true familiarity with its formal explorations.

The Victor Horta Home and Museum was already on my sightseeing agenda. At the tourism office I found a map for the affordable amount of €5: Five Art Nouveau Tours around Brussels. Each color-coded tour concentrates on a particular geographical neighborhood; each house is numbered on the map and listed on an itinerary. Each itinerary, moreover, has a shorter “must see” list that identifies buildings of particular significance. Another list presents the buildings that may be entered, toured, studied. Like the Horta Museum.

The apartment we have rented in the Mayeres House (home and presumably studio of architect Michel Mayeres) on rue Potagère is not on the tour—but we do have a dandy historical marker right on the street. Inside, the remains of woodwork, fireplace surrounds and mantels in a wine-purple and grey-veined stone, and the soaring ceiling all attest to past glory. Marie Resseler in her book Top 100 Art Nouveau/Bruxelles (Editions Aparté, 2010) describes the house as a “mirage in the heart of Saint-Josse,” something out of “a thousand and one nights.” It was the architect’s own home and all architect’s homes end up being a demonstration of what is possible to the end of imagining something beyond that.

We headed toward itineraries 4 and 5 on an unfortunately cold and gray day. The Horta Museum was our primary focus and close behind that a restaurant, Le Chou de Bruxelles on rue de Florence 26. (The restaurant was chosen for its good reputation, its modest prices, and most of all for the guarantee it would be open on a Saturday at noon to two.) From the Janson stop on Tram 92, we walked past the Horta Museum toward rue Africaine, 92.

And a fantasy began to form in my mind. Imagine taking a few million out of the spare change I have no particular use for—yeah, right—and finding one of these Art Nouveau gems in desperate need of restoration. Imagine transforming a wreck that would warm the cockles of hearts of the PBS team on This Old House into a group of apartments, three perhaps, four if there is a fourth floor. Take a few more million out of that spare change and establish a trust for artists, architects, writers and similar creative types, three-month residencies during which they would work on whatever it was that they were working on. The apartments would be large enough to accommodate couples and possibly a kid or two as well—must keep the family together. One apartment, of course, perhaps a studio at the top, would belong to a caretaker—another creative spirit wanting a longer tenure—perhaps up to five years.

I shake myself awake.

As we look at facades, my understanding of what Art Nouveau is begins to change. The houses just don’t look alike. I expected that the tour would land me in some exotic tangle of botanical tendrils, circular window frames, stained glass, mosaic and tangles of ironwork.

But that wasn’t the case.

The houses were in their own way the definition of modernism. They didn’t constitute a modern style but rather a modern spirit. Each one was unique. Some, indeed were Horta-esque in design; others were geometric. Where some were full of surface ornament, others were austere, sculptural, all about the form. Many were self-consciously inventive; several were affectionate in reviving a distinctly Dutch idiom, stepped gables, brickwork, new thoughts on traditional geometry.

As I stood on rue Defacqz, pondering numbers 48 and 50, a friendly young man who clearly learned his English from an Australian came out the door. He needed to put his name on the mailbox and not just on the buzzer to prove to the powers that be that he actually lived there. He lives on the first floor and watches tour groups walk by, moving on foot and debarking from buses. He was interested in the map, interested in learning more about the architecture that brought so many strangers past his home. Were either of these buildings on the “not-to-be-missed list” he asked? “No,” I said, “sorry.” We guffawed.

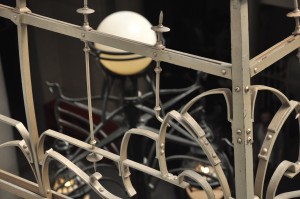

My Dear One and I continued on our way, stopping at Horta’s Tassel House and Hotel Solvay. We made it back to the Horta Museum close to 3:00 to find a line outside and visitors entering two or three at a time. It was both what I knew from the photographs and nothing like what I expected. The cast-iron pillars evoked the organicism of tree trunks and branches and yet spoke of the durability of industrial materials. The footprint of the building is modest; the skylights and top-floor mirrors created a remarkable sense of space.

Before leaving this charming city we paid a visit to the Belgian Comic Strip Centre Museum at rue des Sables, 20, not far from the Place des Martyrs. Whatta place. It pulsates with focused concentration and boisterous enthusiasm and amusement and should be listed high on anyone’s itinerary.

But this is about Art Nouveau. The building, rescued from dereliction to be the home of the museum, is the last great commercial/industrial structure designed by Horta. It was built for Charles Waucquez in 1906, a store for his wholesale fabric and textile business. The business continued until 1970 at which point the decline in the building’s fortunes became precipitous.

In 1984 it was acquired by the State of Belgium with the intention of converting it into a center devoted to comic strip art and history, and a long transformation began. The Art Nouveau glory of the building, its unique details and history were preserved. Spaces on three floors were allocated to a café, book-and-gift shop, study center and library, permanent and changing exhibitions, meeting rooms, rental facilities and offices. It is a wonderful marriage, a remarkable expression of modernity in that both comic strips (and their descendents, the animated film and the graphic novel) and Art Nouveau architecture were, in the 1890s and 1910s signposts of the sea-change overtaking western society. Both were legible to the masses, essentially populist manifestations. Comic strips both entertained and subverted. Industrial technologies used in architecture made glass, iron and steel (to say nothing of electrical lighting) low-cost materials of mass production and modular construction. Capitalism and social revolution, class struggle and the shaping of one’s own destiny all play a part in the historical moment and these magnificent forms of art.

Yes, Art Nouveau is as much about the exaltation of the new as the celebration of the old, the exploitation of the industrial as well as the adoration of the beautiful. It is an architecture that sculpts space while articulating function in innovative ways. Art Nouveau shows the range of the Modernist impulse as well as demonstrating its dedication to historicism and regional identity.

Now I have something new, something I understand myself much better, to tell my students.