They moved with power and precision underneath that great Baroque ceiling as riders sat in near perfect stillness. They ranged from the sooty gray to nearly pure white, manes sometimes braided up, fetlock-length tails blunt-cut at the bottom. Uniforms signaled place in the professional hierarchy: novices in blue hacking jackets, powder-blue shirts and dark ties, helmets; senior riders in brown tail coats, buff breeches, boots extending above the knee and brown tricornes with the badge of the school, the Spanish Riding School.

But it was not the clothing that distinguished the skill of the riders. The most skilled were nearly immobile in the saddle, gloved hands quiet, and legs holding a vertical line out of the stirrup. There was a particular confidence, a kind of agreement between horse and rider about what to do that summons up that tired metaphor of the centaur. But the finer the rider the more absolute the union.

At intervals of thirty minutes or so, they lined up; riders dismounted and grooms buckled halters over the bridles, attached white canvas leads, and walked the horses single-file out of the ring. At the opposite side different horses, some with different riders, entered one at a time, saluted the portrait of the Emperor Charles VI before beginning exercise.

For it was “only” morning exercise and not performance.

The final group were babies, shades of gray betraying their youth and inexperience. Scattered clapping that welcomed the riders unsettled several of the horses, who curvetted and shied. A voice from the loudspeaker reminded us once again not to take photographs or pictures, as that activity distracted both horses and riders. The schooling these youngsters received was basic: trotting and cantering in small circles and figure eights, attention to the aids for changes in lead. The work was elementary but fundamental.

It was two hours I had been waiting for since I was no more than eight years old and it was simply magical.

From there it was only a few minutes to the Kunsthistorisches Museum, a palace of epic ornamentation. The plan was to lunch there and stay until we had seen as much as we could, and were still able to stumble to a taxi that would get us back to the Atla before she pulled away for Budapest. My list of art works I had to see was well served by the “greatest hits” identified on the map, and most were located on floor 1 in a rectangle of rectangular galleries. Lunch powered us around the German, Flemish and Dutch collections; a strudel and coffee break re-energized us for Italy, France and Spain.

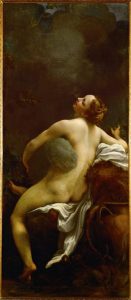

The unexpected? Correggio’s Jupiter and Io (1532-33). Talk about guilty pleasures.

We ducked into floor 0,5 to find Benvenuto Cellini’s gold salt cellar, the one stolen and ultimately retrieved from the box underground in a nearby park. It was bigger, brighter and more colorful than I had ever imagined. Then, in my fatigue, I forgot about the Gemma Augustea. Oh well. Next time.

Vienna demands several next times.