Apparently a few British critics have made the connection between Anna Sewell’s classic, Black Beauty (1877), and Michael Morpurgo’s War Horse, the basis for Stephen Spielberg’s most recent film, but no American reviewer I have encountered has thought to compare them. Perhaps in this country the relationship is not so obvious but Black Beauty belongs to the canon of English children’s books and Michael Morpurgo, O.B.E., held the title of “Children’s Laureate” from 2003 to 2005.

British kiddie-lit has a long and noble history of rural settings and beasts in leading roles: The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1902) and about two dozen other books by Beatrix Potter; The Wind in the Willows (1908) by Kenneth Grahame; A. A. Milne’s Winnie the Pooh (1926); and James Herriot’s stories of the life of a Yorkshire veterinarian that began with All Creatures Great and Small (1972) and included a number of wonderful children’s books. C.S. Lewis’ The Chronicles of Narnia written between 1949 and 1954 fits comfortably among these others as well.

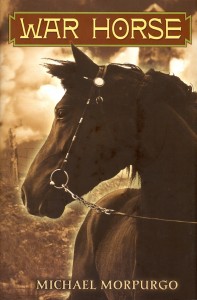

But back to War Horse. When I heard about the book—which I did through articles about the play—I quickly bought a copy and read it. The attraction? It’s a horse story and it’s a work of fiction set in World War One. Readers of this blog already know my fascination with the Great War; friends and family know that I am no less horse-crazy than I was when I was ten years old. We then attended in a performance of the play at Lincoln Center last fall and a few days ago saw the film. All three are splendid, each in its own way.

Joey, the “bright red bay with a black mane and tail… a white cross on his forehead and four white socks that are all even to the last inch” narrates events in much the same voice as Black Beauty. Morpurgo only gives voice to Joey, however, in contrast to Sewell who fills her book with conversations between Black Beauty and his friends, the mare Ginger and the former war-horse, Captain, among others. In fact, Sewell assigns the first speech, if not the first narration of memory, to Black Beauty’s mother, Duchess, who articulates the moral vision that will guide Black Beauty and by extension the child-reader:

“I wish you to pay attention to what I am going to say to you. The colts who live here are very good colts, but they are cart horse colts, and, of course, they have not learned manners. You have been well bred and well born…your grandmother had the sweetest temper of any horse I ever knew, and I think you have never seen me kick or bite. I hope you will grow up gentle and good, and never learn bad ways; do your work with a good will, lift your feet up well when you trot, and never bite or kick even in play.”

It takes only a slight revision to make this the instruction I received from my New England family: “Stand up straight and look people in the eye. Don’t shuffle. Be honest in all you do. Practice kindness and courtesy to all people at all times.” Morpurgo does not have his horses sermonize and instead slips his values into the words and actions of people—English, French and German—who become part of Joey’s life.

Black Beauty’s story spans only a few more years than does Joey’s. Both experience training by loving and patient hands. Both enjoy a relatively exuberant youth although Beauty, at Squire Gordon’s, lives in a more rarified stratum of society. Both eventually encounter a harsh reality filled with struggle, physical pain, and emotional loss. Joey’s boon companion Topthorn collapses after months hauling heavy artillery over nearly impassable terrain; Beauty encounters Ginger in the ranks of hackney-cab horses, a fate that has befallen them both, and later sees her lifeless body hauled away from a dank London street.

There is a happy ending for both. Black Beauty is rescued at a sale by a farmer with an eye for quality, nursed back to health and—miracle of miracles—is acquired by a trio of ladies whose groom is Joe Green, the former stable boy who had been trained up alongside Beauty. Joey tears through No Man’s Land on the Somme, inevitably becoming entangled in barbed wire. He is freed through the efforts of German and English soldiers working together. When the Tommy wins the coin toss, Joey is brought back to safety on the English side of the Front. Another miracle of miracles, the soldier assigned to care for him is none other than Albert, the farm boy who trained him and who ultimately brings him home to Devon.

My Dear One pointed out to me that David Thewlis (Harry Potter’s Remus Lupin and the malevolent Devon landlord with absolute power over the Narracott family, forcing the sale of Joey to the army) played Jerry Barker in the 1994 film version of Black Beauty. In the book, Barker was the kindly hackney-cab driver who has to sell Beauty, beginning the steep slide into misery from which Beauty is saved at the end of the book. I don’t remember Thewlis’ characterization although I am pretty sure I saw the movie. When I reviewed the cast I realized that I would never have missed a movie featuring the likes of Alun Armstrong, Sean Bean, Jim Carter, and Peter Davison— keeping it all alphabetical—to say nothing of Thewlis. I was impressed that my Dear One remembered the actor and role and stunned that I had no recollection of any of it.

How could that be possible?

It is possible for the same reason I can recite The Jabberwocky and The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere, poems I memorized in my childhood, and still know the telephone number at our home in Cleveland Heights from 1957 to 1964 (FA1-2992), but can’t remember pretty much anything from yesterday or the cell phone number I have had for several years now.

There is a more important reason, too. I read War Horse once, soon after seeing the play and the film. I have read Black Beauty scores of times. I still own the copy I was given about fifty years ago, the edition printed by “The Around the World Treasures”. That is the only publication information to be found. Amazon.com suggests that I have the edition put out by the English firm F. Watts in 1959. That seems about right.

I remember every scene in the book, know each character however minor, and recall every moment of the story arc that begins with such hope and threatens to end in tragedy. I remember the color plates at the beginning and the sketchy, ink-and-brush vignettes sprinkled through the book. All of this is locked so securely into my mind that no other visions or interpretations can gain entry. This is way beyond my dislike of a variety of film treatments of well-loved books starting with Gone With the Wind.

This post, however, is not meant to be a paean to the values of the written word.

War Horse—and the various formats into which it has been translated—is an exploration of human choices, the heroics of honor, and the terrible consequences both of choosing selfishness, cruelty and evil, and being unable to see beyond the flaws inherent in all social, political and moral definitions of right and good. It has its limitations as a work of art—as indeed does Black Beauty, a book I personally enjoyed more. Judgments as to what is “art,” though, have their limitations, too.