Planes roar down from the west, above Balboa Park and I-5, to the runways at Lindbergh Field about every minute or so during the day. The first plane seemed loud but in a familiar way—I did, after all, live here in the 1980s.

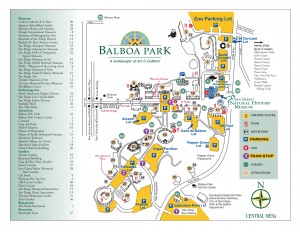

We woke to a pearly Monday sunrise and the promise of a sunny-ish day. Balboa Park, specifically the San Diego Museum of Art, seemed like a good idea. The Museum and then maybe the Botanical Building and the Japanese Friendship Garden. There’s a zillion other places in the Park, of course, from the Zoo to Museum of Photographic Art, from the Hall of Champions, Air and Space and Automotive Museum to collections of cacti, palms and roses, a golf course and archery range. There is, however, only so much territory we can over at the speed with which we move these days, a gait that falls between that of a sloth and snail.

Almost forty years ago I worked in Springfield, Massachusetts, at what were then the George Walter Vincent Smith Art Museum and the Museum of Fine Arts. The MFA is now the Michele and Donald d’Amour Museum of Fine Arts and the GWVS is still the GWVS. Other institutions around that greensward called “The Quadrangle” include the public library, the history museum and other organizations. And to think that all that was there on Mulberry Street. And Chestnut. (It is my understanding that a Dr. Seuss Museum is schedule to join the community in 2016.) My point is that I loved the idea of having a cultural campus where intellectual and creative crossfertilization is all but unavoidable.

Balboa Park is a grander, more ambitious and more irregularly shaped version of that Quadrangle.

We parked at Inspiration Point and screeched and rocked our way aboard the bright green freebie trolley to the Plaza de Panama and the heart of the museum district.

The San Diego Museum of Art is a wonderful institution but the building seems darker and dingier than I remember. This is a structure that needs serious rethinking. The Spanish-Colonial-style building was opened in 1926; new wings appeared in 1966 and 1974. Most galleries—a third of those on the ground level and nearly everything on the second floor—were closed due to an asbestos-removal project. Right now the main attraction is “The Art of Music,” an ambitious exploration of the relationship between art and music—music as subject matter, instruments of works of art, the complex interplay of sound, color and form. The earliest objects are ancient Greek, the most recent psychedelic posters for acid-rock bands and a sound-sculpture installation. Good stuff.

It may be time for a complete rethinking off the physical plant, education and other programs, and the museum’s life and participation in the 21st-century world. Time for a major capital campaign to transform that vision into bricks and mortar. Or steel, glass and concrete. Whatever the future needs.

A trumpet player busking near the Museum’s Panama 66 eatery played the notes of Nature Boy as we departed the home of the Muses for the house of Flora. “I love that song,” I said to My Dear One, “but I don’t remember what it’s called.” He reminded me that it had been recorded famously by Nat “King” Cole and quietly recited the lyrics stored in some unfathomable place in his memory.

There was a boy

A very strange, enchanted boy

They say he wandered very far

Very far, over land and sea

A little shy and sad of eye

But very wise was he.

And then one day,

One magic day he passed my way

While we spoke of many things

Fools and Kings

This he said to me:

The greatest thing you’ll ever learn

Is just to love and be loved in return.

Mallard ducks and a few koi swam by, but the lilies of the famed Lily Pond in front of the Botanical Building had been cut back, were dormant, invisible. Inside the lathe building fading poinsettias disappeared into the green of palms and fig trees. A fiddler had parked himself on the balustrade at one edge of the Pond. He smiled at me and launched into Somewhere Over the Rainbow as we strolled toward the Japanese Friendship Garden.

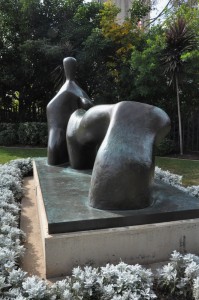

Last week’s torrential rains gouged ruts into the hillsides and ravaged plantings. The Japanese Friendship Garden was full of workers pruning plants, repairing flower beds, staking sausage-shaped netting bolsters filled with chopped straw along the edges of walkways and across slopes. More koi, wildly patterned, brilliantly hued, and some simply enormous eased through crystal water. A Japanese garden does not rely on flowers and foliage for its beauty. It is the forms of rocks and trees, the fall of water and contrast of textures that catch the eye, move the heart.