I normally read Sedaris in places like New Yorker magazine; my husband buys the published collections for me at Christmas or on my birthday, and each piece is a cupcake I can take to bed and not leave crumbs. If I spent more time in the car, maybe I’d listen instead. His style is so diaristic–no, NOT journal-like, thank you Mr. Sedaris for that distinction–that it is hard to remember that these are essays. There is an uncensored stream of consciousness about them that delights and occasionally appalls. Four stars might be a tad high if I were to think about how much surprise and variety I encounter–Sedaris is Sedaris is Sedaris and he is his own and only subject, or at least the vantage point from which other subjects are explored.

Sedaris travels. A lot. And his memories of youth read a bit like travelogues, too. In part, I love the off-kilter perspectives into people and places. In part I am jealous as hell that he so easily sells the summer home in Normandy to buy a desolated heap in West Sussex. How come I can’t do that? After all, I travel whenever I can and when at home browse houses for sale in the Charente in France and look for property in Lithuania, preferably in the Užupis enclave in Vilnius. As they say over and over and over and over again on House Hunters International, “I can see myself” settling in to such a home, getting to know the local baker, butcher and wine merchant.

And letting the idiocyncracies of neighbors inspire wry commentary on my blog and in Christmas Letters? I can do that.

I don’t approach these books in any particular order, I read’em as I get’em and that seems to work our just fine.

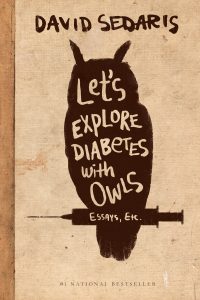

Let’s Explore Diabetes With Owls (Little, Brown and Company, 2013) takes that aimless ramble that doesn’t tell any kind of story until it stops. Themes then make themselves known, patterns in Sedaris’ life and in his reflections on that life emerge. His childhood would seem appalling except that it resulted in extraordinarily tight sibling bonds. A mordant sense of humor seems rooted in obsessions with personal failures, illness and death and yet Sedaris often concludes with a nonconclusion. After his father badgers him into a colonoscopy, Sedaris discovers the pleasures of propofol, the drug that killed Michael Jackson but in the hands of an anaesthesiologist provides a glorious nap.

As I write this, I wish I could say what it’s about. But I can’t. Fun reading, though.