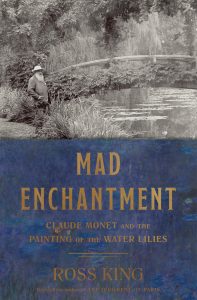

Every time I pick up a Ross King book, it’s longer and weightier. Brunelleschi’s Dome was a little bit of a thing, perfect for reading on a transcontinental flight. Michelangelo and the Pope’s Ceiling was longer but then the Sistine Chapel ceiling is a better documented creation. The Judgment of Paris was longer still and started to drag. Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies (Bloomsbury, 2016) is something of a doorstop. It is not precisely about his paintings of water lilies, nor indeed about the creation of the Grande Décoration, the magical rooms in the Orangerie in Paris.

Every time I pick up a Ross King book, it’s longer and weightier. Brunelleschi’s Dome was a little bit of a thing, perfect for reading on a transcontinental flight. Michelangelo and the Pope’s Ceiling was longer but then the Sistine Chapel ceiling is a better documented creation. The Judgment of Paris was longer still and started to drag. Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies (Bloomsbury, 2016) is something of a doorstop. It is not precisely about his paintings of water lilies, nor indeed about the creation of the Grande Décoration, the magical rooms in the Orangerie in Paris.

I was, however, pleased to find useful illustrations in the front pages: a map of the Seine River and the locales so familiar from Impressionist landscapes; a detailed map of Giverny with notable buildings marked; an excellent plan of Monet’s gardens, including all the various functional structures; and the Monet-Hoschedé family tree showing the children, stepchildren, their spouses and the grandchildren. Unsurprisingly, I referred back to several of these diagrams during the course of my reading.

But the story. Chapter One, “The Tiger and The Hedgehog,” opens with the background that sets the relationship between that giant of French history, Georges Clemenceau, and the master of French Impressionism, Claude Monet. In the end, much of the narrative winds around these men, their long and devoted friendship as well as the stresses that friendship endured. For me, the “painting of the water lilies” seems to be less the subject of the book than a means for exploring this relationship. There are numerous points where it seems that Clemenceau’s life and his exploits as president and minister of war during World War I tug at the author’s attention more forcefully than do Monet’s activities in the studio.

So the book was a bit of a disappointment. I thought it was going to focus on the motif of water lilies in Monet’s work and attention to that was fragmentary and confusing. I thought… well,,, I don’t know what exactly I thought, but I found myself going down this path and that, wondering why precisely the tangent was relevant. In the end I felt I had learned something—but what exactly I am not quite sure.

In some ways I wish I had read the book a year ago, in 2017, before finally making our way to Monet’s home in Giverny and to the revitalized and refreshed Musée de l’Orangerie which had been closed in 2002. I am not a devotee of Impressionism in general or Monet in particular. I prefer Monet’s efforts from the 1860s to the popular series of the 1880s and 1890s. My taste for the paintings of nymphéas came along later, a part, no doubt, of my growing devotion to gardens.

I had not realized, at the Orangerie, that the Grande Décoration was not the product of a site-specific installation, that the selection of the canvases presented in the two rooms was ultimately a matter of choosing what worked in Monet’s mind once the architecture housing them had been fully established. I admit to some confusion when I encountered other immense canvases from the group at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, or the exhibition “Painting the Modern Garden: Monet to Matisse” at the Cleveland Museum of Art. Just how many of those things were there, anyway? Having seen the renovated spaces with Monet’s gardens fresh on my mind, I am sad to realize that Monet never saw the ultimate results of the project that consumed the final decade of his life.

The house and gardens were, in fact, extraordinary. The dining room and kitchen were as buttercup-yellow and cobalt-blue as I had imagined. The allée of roses, while not in bloom, anchored the beds filled with tulips, iris, phlox, poppies, anemones and so much more. As I framed images of the pond, I sensed good Monsieur M. himself whispering in my ear about the best views and reminding me to look into the depths, “the luminous abyss” and not just let my eyes skip across the surface like smooth stones flung from a child’s hand.

The house and gardens were, in fact, extraordinary. The dining room and kitchen were as buttercup-yellow and cobalt-blue as I had imagined. The allée of roses, while not in bloom, anchored the beds filled with tulips, iris, phlox, poppies, anemones and so much more. As I framed images of the pond, I sensed good Monsieur M. himself whispering in my ear about the best views and reminding me to look into the depths, “the luminous abyss” and not just let my eyes skip across the surface like smooth stones flung from a child’s hand.

A good book? Well, it’s a worthy addition to the vast bibliography that keeps expanding. A good read? For a general audience book, it depends perhaps too much on readers’ familiarity with history, that of French Impressionism, French culture in general in the early 20th century, the emergence of Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse as the new leaders of modernism, the background and battles of World War I, and more.

My judgment. No “mad enchantment” but now that I have finished it, I like it more than I did while I was reading it.