I expected the village of Žiežmariai to be a quick stop. My target was the church, St James the Apostle, where so many Tomkuses had been baptized, married and seen off to the hereafter. The wooden prayer house those ancestors would have known was replaced in 1924 by the brick edifice I encountered.

St. James the Apostle

The single tower of the current St. James beckoned a mile or two before I arrived at the center of town. The church sits on its lot, inside a wall, with a handful of gravestones, a crucifix and a traditional carving. Closed, of course, although some kind of activity had clearly just concluded.

I imagine the Tomkuses who worshipped there prior to World War I would have found the new building very grand, very modern.

I wondered how they might have traveled from Meižonys to Žiežmariai. It‘s about twelve miles, less than twenty minutes by car. The trip would take over two and a half hours by foot, however, via a causeway across a pond, a causeway which might or might not have existed then.

The Synagogue

I saw a sign for a synagogue. I found it tucked behind some buildings. A staff member invited me in and shared the story of the restoration completed in 2021. It is one of the only surviving wooden synagogues in Lithuania, and the largest.

It is exquisite. The proportions are perfect. Light was palpable throughout. And the smell! Every breath filled me with the awareness of wood and life.

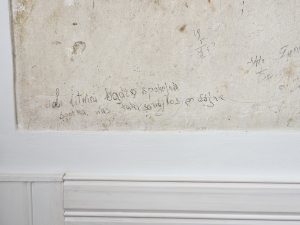

Where original surfaces could be preserved, they were. The decorative program replicates as exactly as possible the original.

And to imagine that this building—spacious for a house of worship but not huge—was the ghetto into which the women, children and elders of that community were crammed prior to their executions by the Nazis.

The Movie Theater

Next to the synagogue is a structure plain on the back but quite elegant on the front. It was the Jewish movie theater.

Both buildings are in the center of town. Around the green are a number of old houses, typical of the wooden homes built in the 19th century that survive in small towns all over Lithuania. Certainly I saw many similar houses in Balbieriškis. Some are occupied now; some not. But who lived in them in the 1920s, 1930s and into the 1940s?

Were the synagogue and movie theater the hub of a thriving Jewish population? I imagine so.

Missing People

In France, along the Western Front, they have signs for “Villages Détruites.” These are villages which once existed but were expunged as the battles of World War I (and in some cases World War II) moved back and forth across them, grinding them into oblivion. The French government has assigned them this official designation.

One wonders if Lithuania should not do the same for the countless towns and villages whose Jewish communities were eradicated. Could there be standardized historical markers stating the Jewish population in, say, 1939 at the onset of Nazi aggression, and in 1945 or 1946, following surrender?

Balbieriškis

Rymantas Sidaravičius has done something very like that in the Balbieriškis Tolerance Center, where he is director. A historian by training, Sidaravičius has done exhaustive research into the Jewish people who once made Balbieriškis a bustling town. He knows the atrocities that were committed and where they took place; he was instrumental in locating the exact site of the massacre of 144 Jews in Jieznas in the Prienai region on August 9, 1941, and placing a marker there.

In the Tolerance Center are images, documents and artifacts. Certainly, no comparison struck me as forcefully as that of the houses along Vilnius Street, the main street of Balbieriškis. There were more than 1200 Jews in the village before the Nazis, and about five hundred or so non-Jews. In 2011, it had a total population of 966, and the number has dropped since.

Thanks to people like Rymantas Sidaravičius, local children learn a fuller history than they did before. I cannot help but feel, though, that this fuller, truer, more difficult history is something too many people, at least too many Americans, don’t want to hear.

Too Small to Remember

The immensity of the Holocaust overwhelms. The sheer numbers are outside my ability, at least, to fully grasp. The concentration camps remain in our awareness, too much as sites of tourism. Large cities—Vilnius and Jerusalem, New York City, Washington DC and Budapest—are home to extraordinary memorial and education centers.

Yet it is, perhaps, in the small towns and villages, the places easily forgotten as the back of nowhere, that the horror seems most tangible and inescapable.