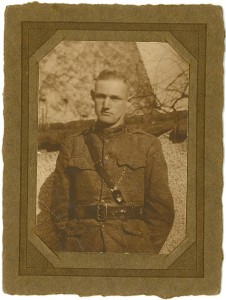

So much of this trip has been about discovering a grandfather who was never a part of my memory. David Sanford Cutler died suddenly from what may have been a staph infection in 1926. His sons Calvin (my father) and David were only two and four years old respectively. His widow Hazel, my Granny, remarried and Arthur Pope was my Gramps, just as their adopted son Stephen was my Uncle Steve.

I learned so little about David as I was growing up. It was my understanding that Cambridge, Massachusetts,was the place he met Granny; I believe he was a physically frail man, possibly diabetic, and that being gassed during the War contributed to his early death; I knew that Granny planned to be buried next to him in Evergreen Cemetery in West Medway, Massachusetts, but that Uncle Steve, at that point her closest next-of-kin, wanted her interred in Hingham with Gramps where he could eventually join them.

The wartime letters conserved by his family–and ultimately given to me–told me much. I learned about David’s experience at Officer Training School at Plattsburgh, New York, and the life he led in France from October 1917 to the first months of 1919. I learned how deeply he cared for Granny and how important it was to him that his family, particularly his mother and sister Helen, look after her.

I think he was a kind man at heart, but self-deprecating and sly of wit. His letters sound oddly like the memories I have of my father telling stories. He pooh-poohed his hardships and made nothing of his injuries.

Learning the facts of his enlistment gave his biography a structure. David was commissioned a 2nd lieutenant in the 26th Division (the “Yankee Division”), 52nd Brigade, 103rd Infantry (although he was transferred to the 101st Infantry in the spring of 1918), Company D. From here I found my way to Michael Shay’s The Yankee Division in the First World War: In the Highest Tradition and even more helpfully to Soldier’s Mail: Letters Home from a Yankee Doughboy 1916-1919, a truly absorbing and invaluable resource on all things Yankee Division.

All this brought us, my Dear One and me, back to Chateau-Thierry.

We had visited Paul Cret’s austere—and in my opinion imperialist—monument on Hill 204 in 2002. On that day it rained lightly and then, as the sun broke through the clouds, a rainbow arched over the horizon to the northeast. This time cold fog made that cold structure colder in so many ways.

The enormous allegorical figures of America and France hand-in-hand struck me as just wrong. Despite their twin scale and visages, America wields a sword and visually steps forward as France, in her Revolutionary cap and simple breastplate, seems to take courage from her more powerful sister. To me, both an admirer of Cret’s architecture and a patriotic American, this isn’t the relationship I believe existed or would convey to posterity.

We left there and went to the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery and Memorial in Belleau. In the warm confines of the Visitor’s Room, a space that reminded me of a study or den I might have sat in fifty years ago, we looked through books, examined the alphabetical roster of soldiers buried in the cemetery, and studied the map of the events around Chateau-Thierry from July to August 1918. Flora Nicolas, the Cemetery Assistant—a young woman whose smile and profound grasp of her subject reminds me of Karine at Beaumont-Hamel—offered a summary of the war, the situation in the Aisne-Marne from 1914-1918 and the Aisne-Marne Offensive of July 18, 1918. I explained a little about David and she skillfully wove the story of the 26th into the narrative that took us through the events of that summer.

Before she left for lunch she gave us the key to the 26th Division Memorial Church of Belleau, the small church funded by the donation of a day’s pay by each surviving member of the Division. This church replaces the one in the center of the village of Belleau that was used as a lookout station and sniper nest by the Germans. The old church’s spire, visible from a long distance, was targeted by the 26th’s artillery and completely destroyed. The rebuilt church is a memorial to the division’s dead and an apology and gift of thanks to the people of Belleau.

This is the second time I have been given a key to a church in France. The first time was in a village with a renowned church, un hameau tout petit, and what I remember was the weight and size of the iron key, the lunch we enjoyed on the hillside behind the church, and the clunk of the key as we dropped it in the mail box per instructions. Most of all I remember the honor I felt with the trust extended by the folks at the Mairie.

Flora helped me understand, really for the first time, the shape of the battle in that region, the line that marked the German entrenchment in 1914, the position of the Chemin des Dames, and the great aneurysm in the Front that threatened Paris in 1914 and terrifyingly again in 1918. I saw what that meant to Pop as an ambulancier attached to the 124th division of the 4th Army Corps of the 4thArmy, “General Gouraud’s army.”

She also helped me make sense of the oblique references in David’s letters. As an officer, one of his main responsibilities was the censorship of the enlisted men’s letters; his own letters are frustratingly thin on detail, although he seems to have littered them with clues that in some miraculously way his mother and sister were able to decode. If only their letters had survived!

And only if I had known that the memories of elders, friends and family are a gift that does not last. A question posed many years ago in an art magazine asked, “If you could have an hour with any artist of any era, who would you choose and what would you ask?”

Pop, David, I have so many questions. An hour would hardly do—and would I be able to get a word in edgewise once you two started chatting?