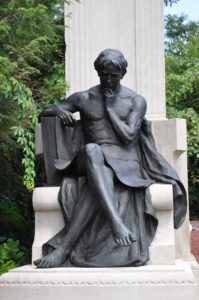

On the other side of the Johns Hopkins monument from the allegory of knowledge--imagined as male--is an allegory of healing--imagined as female.

We—my Dear One and I—attended the 121st Turnbull Lecture at Johns Hopkins University on the evening of February 28. The speaker, John Irwin, a senior faculty member in the Writing Seminars, has just published a book on the poetry of Hart Crane and his topic was “Building the Virgin: The Triple Female Archetype in Hart Crane’s The Bridge.”

The talk was a tour de force, sixty minutes of intricate and tightly knit argument that presented this poem as the early modernist epic of American culture. Irwin argued that allusions to works by poets from Americans Emma Lazarus, Walt Whitman and Edgar Allen Poe to the Englishman Matthew Arnold and Ovid in ancient Rome illuminated Crane’s nationalism as well as his engagement with tradition in creating something modern. That Crane had read these writers and internalized their imagery was indisputable; it was less clear to me that Crane deliberately invoked all of them.

By the end of that hour, my little grey cells were puffing with effort. I have not listened so carefully to material so unfamiliar and difficult in many a year, and the exertion packed a real endorphin wallop.

I am not sure I bought into Professor Irwin’s argument in the end. I have not read The Bridge—in fact my only encounter with Crane’s poetry took place in a high-school English class my senior year. There was a part of me that was enmeshed in thoughts about patriarchy and the oppression of women and the problematic persistence of the “virgin ideal,” something that has been considerably more useful and valuable to fathers and husbands than to the virgins themselves. Isn’t this an intellectualization of the trope “Women should be cooks in the kitchen, ladies in the drawing room and whores in the bedroom”?

I did, however, make a note about some ideas to bring up the next time I teach Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1538) in my Renaissance to 1855 class.

For all his alcoholism, depression and homosexual turmoil, Hart Crane was a modernist intent on creating a modern art that advanced and expanded the boundaries of great art. Yes, Crane understood the Renaissance representation of Jesus, in showing the way to the Promised Land of heaven supplanting Moses who brought his people to the geographical Promised Land. Like Picasso or Matisse or Kandinsky, Crane did not seek to destroy the Old Masters but instead to join their pantheon as a Modern Master. In so many ways, however, the Modernist Enterprise—a very admirable and thrilling enterprise—was also a masculine and frequently misogynistic enterprise. I don’t know that this matters; I just wonder if Crane’s heroic ambitions should not be framed, in part, by the testosterone-laden circle in which he competed.

I mentioned my musings to my Dear One and allowed as how I probably would not share them with Professor Irwin or his colleagues; my Dear One allowed as how that was probably a good idea.

Professor Irwin’s talk did get me to thinking, however, about the way that we read, and the books and poems that are embedded in our psyches, which constitute the masonry that upholds both our imaginative and our analytical faculties.

And who are the writers, what are the works at the foundation of my thought processes? What works provide the catch phrases, the gestalt of my ideation?

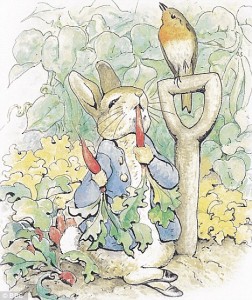

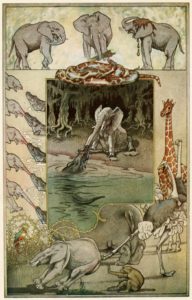

Beatrix Potter’s Peter Rabbit, certainly, who, “feeling rather sick went to look for some parsley.” It was not the “’satiable curtiosity” of Kipling’s Elephant’s Child that gave Peter digestive upset but rather his boundless appetite for Mr. McGregor’s lettuces, French beans and radishes. The Elephant’s Child almost became the dinner of the crocodile who lived on the banks of the great grey-green, greasy Limpopo River all set-about with fever trees, and whose dining habits fascinated him so. Peter Rabbit nearly became, as his feckless father had before him, the filling for one of Mrs. McGregor’s pastries.

The Elephant's Child, thoroughly spanked for his "'satiable curtiosity" still wanted to know what the Crocodile has for dinner.

The source of my penchant for culinary metaphors?

It was not that there was a shortage of books at the summer cottage on Squam Lake, but it is nonetheless true that I read The Swiss Family Robinson by Johann David Wyss more times than makes any sense, and enough times that even at a tender age I found the Disney bowdlerization appalling. Similarly, the copy of Jane Eyre was well thumbed and it was not until the most recent BBC adaptation that I could believe that the writer and director had read Charlotte Brontë’s classic as often or, might I say, as perceptively as I had.

The two intersect in my unshakeable belief that education is as useful as the student decides to make it and that every talent eventually comes in handy.

Jane goes from learning to duck when books are lobbed at her to parlaying the punishing instruction at Lowood School into a job as a governess where, a couple of fires and a few personal detours later, she marries Mr. Rochester and lives, presumably, happily ever after. The ability to paint striking watercolors touched by Symbolist weirdness is a plus as well.

The sturdy Robinson family rescues a trunk of books from the sinking ship they have just abandoned. This reference library, in conjunction with father’s knowledge and a gene pool blessed with a surfeit of creative ingenuity, provides all that is needed for the establishment of a progressive and environmentally respectful social Utopia. A particularly memorable episode involves the catching of sturgeon. The father produces several barrels of excellent “caviar” and also extracts isinglass from the leftover bladders from which he makes transparent panels for the windows in their tree house.

Jane and the family Robinson indeed are alchemists who seem to find in leaden existence golden opportunity. They are the folk who turn lemons into lemonade, the cardsharps who know it is less about the cards one is dealt and more about the way they are played.

Is this where I became a Pollyanna determined to find the silver lining and celebrate the half-full condition of my glass?

Or was my character molded by the model of Black Beauty? Anna Sewell’s equine hero hews to the moral values and and sense of noblesse oblige instilled in him by old Duchess back in that pasture before his fourth birthday.

I wish I could say that I consciously turn to these sources as I teach and write and make the decisions that bring about the turns in my road.

But I cannot.

A part of me wonders, moreover, how specific Hart Crane was in his allusions, how conscious he was of the well from which he dipped his words and world view.

I also wonder what Hart Crane read when he was a boy.