My brother the Boston Lawyer mentioned a couple months ago that he was reading Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson (Simon & Schuster, 2017). I thought that was an interesting choice for him, a little off-road considering his normal preferences. When My Dear One gave me a copy for Christmas, I emailed a question: “Why choose this book?”

His answer was exactly what I guessed it would be: “I heard about it on NPR and of course it sounded interesting. But mostly the subject was dead center of a large knowledge gap.” The Boston Lawyer and I are really one of a piece. He went on: “I just finished reading it last week. I loved every page and learned so much.” I’m an art historian and I didn’t think I had much of a knowledge gap there. I learned a lot, too. My copy is also all a-flutter with little yellow post-it notes.

This book reads like a blockbuster exhibition. In any good blockbuster exhibition, from The Treasures of Tutankhamen, which traveled to six American museums between November 1976 and April 1979, or Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty in 2011 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, scholarship and popular appeal forge a complex marriage. Isaacson chose a subject at least superficially familiar to a broad swath of the public and he and his publisher had impeccable timing. Recent years have been full of Leonardo discoveries and controversies. In the last twelve months the rediscovered and restored Salvator Mundi panel sold for something over $450 million and the hullaballoo around the auction, though, got people talking about art, art values, and Leonardo da Vinci.

I do not damn the book with faint praise, however. Isaacson is a historian- biographer rather than an art historian-critic and this is one of the book’s strengths. Simon & Schuster spent wisely on design and illustration. I have nits to pick: works illustrated are not dated and drawings are not clearly associated with particular sketchbooks or collections; captions leave much room for improvement. Isaacson sometimes fails to align his descriptions with illustrations. Figure 141, one of the deluge drawings, is summarized with its mate as belonging to a “series made with black chalk, sometimes finished with ink.” The illustration shows a rich red coloration. Is the ink not black, then? Or is the reader supposed to infer that this illustration is one that was “tinted with a color wash”? For heaven’s sake, just be specific about what I am looking at.

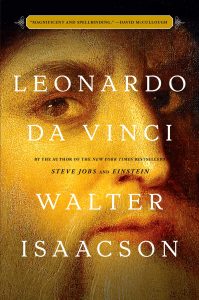

The book includes lots of support for readers unsteady about the time and context. Front pages include a cast of key characters and their dates; a brief explanation of currency in Italy and a sense of what a coin would be worth in today’s dollar; a note about the portrait of Leonardo used for the cover design; a list of the primary periods of Leonardo’s life; and an excellent and colorful timeline that pictorializes those periods.

In his writing, Isaacson pretty well hews to that timeline. The focus is on what Leonard was doing or feeling, his important social and financial connections. Discussion of Leonardo’s drawings explores the artist’s obsessions, hopes, dreams, discouragements. Thus the drawings and notes provide the structure in which the great paintings, unfinished and finished, might be understood. Isaacson does a particularly good job situating the artist’s homosexuality and personal psychology in context without letting those issues take over the narrative.

If there is something anyone can take away from this biography, it is the value of sharing, collaboration, mutual support. Leonardo’s family members, friends, lovers, models, associates, patrons all contributed to that extraordinary ferment that cradled, nurtured and challenged Leonardo’s genius. Isaacson doesn’t fuss about the projects and ideas not seen through to conclusion. What he does, instead, is question what “finish” means and whether the completion of a project is a marker of its success.

After all, a destination that looks predictable and inevitable may be neither of those things and that is probably a good thing.