The painting on that wall in the Tisch Galleries at the Metropolitan Museum of Art would not let me move on.

Only a couple of years ago, My Dear One and I had wandered the maze of discontinuous hallways and Escher-like stairs that constitute today’s Louvre Museum to find the Delacroix’s and Théodore Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa. We did, finally, arrive in that gallery. The Raft, that compilation of the dead, the dying and the desperately hopeful that created such a stir at the 1819 Salon is the work of art I remember most vividly—more than the Mona Lisa, more than the Winged Victory of Samothrace—from my first encounter with the Louvre when I was barely eighteen. Delacroix’s evocation of revolution, Victory Leading the People (1830), now looks almost too relevant in this Age of Trumpublicanism. Some years ago, a former student on his first excursion over the Pond sent me a postcard—of Victory.

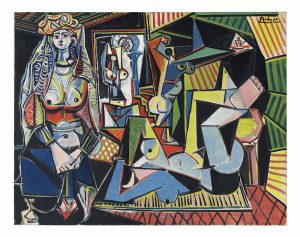

Recently I had been thinking a lot about The Women of Algiers. While organizing topics for my Cubism seminar, I was trying to think about how to present late Picasso, the works from Guernica (1937) on. I looked at all those cubist variations on the Old Masters, on Velázquez, on Édouard Manet and especially on Delacroix and the Women, of which he produced fifteen versions over the course of about a year. In exploring those versions I spent time looking at what Picasso looked at: this odalisque or that, the servant, the carpet, the hookah, the colors–and that door in the background.

Many contemporaneous critics found Delacroix’s compositional strategies lacking, to put it kindly. So many figures, so much violent action. Such narrative disorganization, such an absence of hierarchy. I don’t disagree. I find myself staring bleakly into the smoking ruins of The Massacre of Chios (1824), past the dead and dying, barely pausing to note the pathos of the infant trying to suckle at a breast where a heart no long beats, past even the salacious abduction of the blonde and virginal Greek and the satanic Turk on the rearing warhorse who carries her off. The Death of Sardanapaulus (1827) is a Bacchanalian ring-around-the-rosy, all scarlet expanse of couch, of gold and pale flesh that constantly distract but does not hold my attention. The titular king creates his own funeral pyre from the concubines and jewels and horses and slaves that had expressed the power he had lost, the ephemera that constituted his only sense of self.

These also were works of Delacroix’s ambitious youth. They expressed, among other things, the emergent understanding that modernism had to be the “shock of the new.” Bigger was also, if not better, a statement of importance, a metric for measuring subjects, ideas and skills. In 1832 Delacroix rode France’s invasion of North Africa as a tourist into Morocco and Algeria. He filled his notebooks with sketches, watercolors, notations and observations. His perceptions were western and Romantic and he mined his notebooks and memories for the final three decades of his life.

The door. That red-framed door, or possibly a window, in the buff stone wall, slightly ajar, with something not quite visible beyond. Furnishings? A person?

There is so much to admire about this painting. That door, however, has made me love this painting.

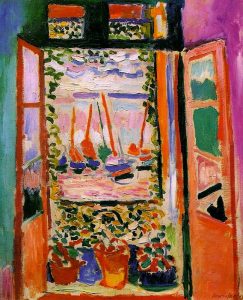

I think Henri Matisse looked at that door. Doors and windows, especially the French doors with their shutters so common in Provence, were for him the magical portal between the interior space of artifice and the exterior space of nature central. There is the Open Window, Collioure (1905) where walls and glass-paneled doors frame the sailboats and infinity of sky and water beyond. In the 1940s Matisse was still gazing out the window. Much is made of the nudes that Matisse painted under the influence of Delacroix. But look at that fenestration, feel the breeze, bask in the sun that vanquishes the shadows inside.

Picasso felt the loss keenly when Matisse died in 1954. They were frenemies, having vied for leadership of the avant-garde before 1910 and engaged in aesthetic combat during the teens and twenties. Maybe beyond; certainly the Museum of Modern Art tried to make an argument for that in the Picasso/Matisse show of 2003. Picasso, though, acknowledged the respect and need implicit in that relationship. When Picasso turned to Delacroix and The Women of Algiers, he was turning, in a way, to that conversation that he could not let end, a door that would never close. He also felt the magic of Delacroix’s door.

In The Women of Algiers in their Apartment, the door is like a fifth presence. The red rails and stiles–not exactly vermilion or crimson or cayenne–frame brown wood panels edged in black. A drape woven with the same red has been pulled to the side like a theater curtain that opens on a stage. The play however, is not centered on these indolent women with their hookah pipe and attentive black slave. The drama offered lies beyond, through the portal which has cracked open. The painter steps aside; viewers must carry on alone.

For me, this is truly one of Delacroix’s masterpieces, one of the three or four paintings in which his draftsmanship, his brilliance with a brush, his orchestration of color, sensuousness of subject and imaginative narrative are in balance but not stasis, tension but not combat, harmony but one sharpened with a dissonance on the brink of resolution. The painting is big, not monumental but big with the largeness of events transpiring only a few feet away.