I read Sy Montgomery’s Soul of an Octopus (2016) and it permanently decreased my options on the sushi menu. The Good Good Pig: The Extraordinary Life of Christopher Hogwood (Ballantine/Random House, 2006) may not permanently put me off pork, but it will make me consider the nature of each life that ends up on my dinner plate.

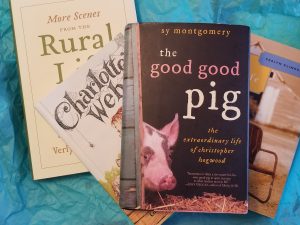

The Good Good Pig is now filed on that section of my memory shelves that holds Verlyn Klinkenborg’s The Rural Life (and More Scenes From the Rural Life), a pair of incomparable posthumous articles by Maxine Kumin published in The American Scholar, “Our Farm, My Inspiration” and “The Making of PoBiz Farm,” dated 8 December 2013 and 11 March, 2014 respectively, and, of course, E.B. White’s immortal Charlotte’s Web. To these I might add the poetry of Robert Frost (1874-1963) and especially Donald Hall (b.1928). These are the descriptions, meditations, grumps and rhapsodies that echo in my own sense of the rural landscape and most especially that of New Hampshire.

And whenever animals figure prominently in the tale—well, even better.

Christopher Hogwood, namesake of the prominent conductor (1941-2014), was a “runt among runts,” a sick and ailing piglet that still fit in a shoebox when his littermates were tipping the scales at thirty-five pounds and more. Like White’s Wilbur in Charlotte’s Web, Christopher Hogwood should have met an early demise in the pragmatic cruelty of the barnyard. But he didn’t. With regular worming and an extraordinary quality and quantity of slop provided by the denizens of Hancock, New Hampshire, and quite some distance beyond, he not only caught up with pigs that had a more auspicious start, he topped out at a massive seven hundred and fifty pounds of cherished and indulged boar.

By the age of nine, and becoming arthritic, Chris had assumed a shape the vet described delicately as “somewhat…amorphous” and had to shed a hundred pounds. Much of the book is devoted to finding food for this grand gourmand, discovering his preferences and discovering that pigs can indeed move from omnivorous gluttony to extreme pickiness. At this point however, there is also a focus on delectation, on selecting the most enticing morsels and savoring each mouthful.

When I was quite young, we had the most marvelous cleaning lady, Beatrice Moody, who kept our summer house from descending into utter filth and chaos. Mrs. Moody was about forty-five, which seemed very old to me, and she could whistle. As she began sweeping the floors or coping with a sink full of dishes, trilling, lilting music would fill the house, tunes I didn’t recognize but that made me think the Camp had been taken over by some avian divinity. Mrs. Moody and her husband lived in Ashland and had a collie dog named Isabella, known as Izzy, and at least one summer, a pig. All that vacation we collected our corncobs, old fruit, leftover salad, and the like, and bagged it up to take over to the pig. I remember the pig as a basic pink pig, but I don’t know if that is correct. We knew that one day in the fall that fascinating creature would become a collection of white paper packets in Mrs. Moody’s freezer, but I at least preferred not to dwell on such a disturbing thought.

I hadn’t thought of that pig more than a dozen times in the last half-century but I’m sure he was a good, good pig, too.

A question raised at the beginning of the book is how long a pig can live; nearly all pigs are destined for the table and don’t celebrate their first birthday. As Montgomery points out, one cannot know the middle without first arriving at the end. When Christopher Hogwood died peacefully in his sleep in his fourteenth year, that seemed to be an answer. His bumptious, celebrated, unavoidable presence in the daily life of Hancock is also a means for telling other stories, of indulging life and mourning death, or reframing “family” to include any creature that finds a niche in the kinship narrative.