The phrase “police brutality” has been part of my vocabulary since at least 1968.

That is the year that the Democratic Presidential Convention faced immense political challenges inside the International Amphitheatre and protesters clashed with literally thousands of police and National Guard armed and carrying riot gear. It was fully militarized police back then. The implications of that militarization were made tragically clear at Kent State University in Ohio in May 4, 1970.

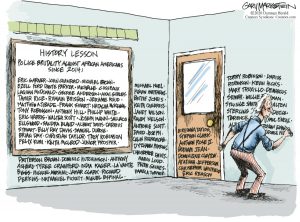

George Floyd died under Officer Derek Chauvin’s knee in Minneapolis on May 25, 2020. His was the most recent—and because of video recordings the most grotesque—of a string of killings by the police of unarmed people of color. The assaults and resulting death tolls seem to be accelerating. There was the beating of Rodney King in Los Angeles in 1991. A very incomplete list of deaths would include Amadou Diallo (NYC, 1999), Oscar Grant (CA, 2005), Kelly Thomas (CA, 2011), Michael Brown (MO, 2014), Eric Garner (2014), Tamir Rice (OH, 2014), Freddie Gray (MD, 2015), Walter Scott (NC, 2015), Philando Castile (MN, 2016), Terence Crutcher (OK, 2016) Jean Botham (TX, 2018) and Antwon Rose II (PA, 2018), Atatiana Jefferson (TX, 2019) and William Green (MD, 2020), 2020.

It’s In The System

That American law enforcement has treated people of color with a kind of moral disdain and casual cruelty is certainly evident to most of us. Behind the shield of upholding the law, too many officers have paid no penalty for actions that were arguably crimes. Given the legal shelter of “limited immunity,” police are only enforcing laws that are more often than not, racist in its structure and frequently racist in its intent. On the most recent Last Week Tonight, host John Oliver quoted this assertion by “an Alabama planter in the wake of Emancipation:”

We have the power to pass stringent police laws to govern the Negroes—this is a blessing—for they must be controlled in some way or white people cannot live among them.

Several of these terrible encounters provoked peaceful protests as well as riots. It also seems that American law enforcement often is unable to distinguish between peaceful protest and a riot—often turning the former into the latter.

George Floyd’s death may be—and I desperately hope it is—the one that forces genuine and lasting change.

I Love John Oliver

This brings me to John Oliver whose Last Week Tonight won an Emmy for “Outstanding Variety Talk Series & Writing for a Variety Series” in 2019—and 2018, 2017 and 2016. Pretty much for the entire Trump administration as well as the election year leading up to it.

I admit it. I’m a fan. I fell for that dweeby charm when I first encountered him on the sit-com Community in the role of Ian Duncan, psychology professor. Last Week Tonight airs after our bedtime but we record it and enjoy it with Monday lunch. I even bought his charming fable of a gay rabbit, A Day in the Life of Marlon Bundo.

Oliver’s sense of humor is, as he frequently points out, “British.” Each show takes the mickey out of someone or something the way my classmates at my English boarding school took the mickey out of me—relentlessly. While hardly pitch-perfect, his distinctive mix of analysis of issues and ecumenical roasting of all and sundry associated with film, television, news, business and popular culture is for me pure entertainment.

The Medium Shapes The Message

Since the beginning of the current season, Oliver and his team, like so many businesses, have been working separately and splicing together a program that is offered in the isolation of a “white space,” without audience, without any sense that one sits there along with a raucous and like-minded crew.

So now, John Oliver, looking into the camera, is looking directly at me. He is talking to me only, or so it seems. If there is a laugh or a groan or a gasp, it comes only from me and in that moment, it seems that he hears it and acknowledges it. To me.

This was never truer than during the episode aired on June 8. It was about police, policing, brutality and what it might mean to change from a system engineered on systemic racism to one in which public protection and service is paramount. And by “public” I mean every single person in the community equally and at all times.

I sat. I listened. I imagined what defunding and demilitarizing the police might entail. I wondered if we could learn to say, “public protection” rather than “policing,” and if we could do that, whether changing those words would, in any way, change our hearts, minds and assumptions.

Somehow, Oliver has filled the space left behind when the live audience was locked out; he has made the experience for the viewer more intense, more personal and more relevant. There are still jokes but they are much, much darker. He still makes liberal use of profanity. Clips mined from social media and news agencies still have a part to play. It is his words, though, and his eyes, that hold me.

We Need To Know

Oliver has always wrapped our need to know this information in a certain urgency. Trump has dubbed himself “your president of law and order.” He has also thanked himself ordering a peaceful gathering in Lafayette Park dispersed with violence so that he could walk to the doorstep of “the Church of the Presidents,” St. John’s Episcopal Church, and brandish a bible with the gesture of a tin-pot dictator.

We the people of the United States have an extremely urgent need to know what is going on and why and whether the actions of the head of state are lawful, let along moral or honorable. There are only so many printed and electronic news sources I can read. I’ll see what insights John Oliver can offer each week about last week.