This was the branch that most frightened me, the one most perfectly positioned to do irreparable harm to the monument. Lower and smaller branches had already been removed, opening space around the slender column surmounted by its neoclassical urn. Four of us—two on the ground, two in the tree—studied the weight of the limb, its length and angle of growth, the terrible threat it posed. After much discussion and thought, the red strapping was secured to the branch as far out as young Daniel dared reach; Jim began to saw; I braced myself and pulled the strapping taught.

“Stop! Stop! Stop!” cried Chris as he saw the finial on the urn bobble. Jim called for more tension on the strapping and David joined me. Together we pulled the branch another few inches from the carved marble and I gritted my teeth at the crushing pain in my hand. It was not more than another minute or two before the long, heavy limb dangled safely distant from the monument. David and I loosened our grips and lowered it toward Chris who guided it to the ground.

For the first time in what had to be many decades, the Sanford monument stood tall and fully in view, no longer encircled by the branches, obscured by the needles that spiral in blue dark green fringes around their twigs. I examined my right palm; two red dots below the ring and middle fingers of my right hand marked blood vessels that broke under the pressure. I looked around and announced that it was time for lunch.

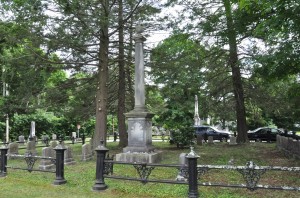

Somewhere during the early 1970s I think it was, I drove my Great-Aunt Helen to West Medway for a visit. We stopped at Evergreen Cemetery where her family is interred and also at Thayercroft, the house where her mother (née Thayer) had lived in the last years of her life. It was on that trip, as I stood by “The Enclosure,” an ornamental iron fence set round the Sanford monument, that I had an epiphany: these people, these spectral ancestors, were so real that they were dead. I felt then the allure of family arcana that Helen had long studied.

The news that the Medway Community Church would be celebrating the bicentennial of their “Church on Rabbit Hill” got me to thinking. My father’s paternal line is complexly rooted in Medway, a town founded in 1713; wouldn’t it be fun to combine that event with a tidy-up in the cemetery and maybe a little excursion to some of the sites of family significance. After all, sixteen of the thirty-three signers of the covenant that established the church in 1750 are related to us by blood or marriage. The Church on Rabbit Hill was the “new church” though. My fifth-great-grandfather David Sanford (1737-1810) led the congregation at its original home for thirty-seven years.

And so it happened. Participants included me and My Dear One; my brother Jim and two of his sons, Chris and Dan; Dan’s girlfriend Cecily; my sister’s daughter Stefanie and her son Henry; and our cousin David.

I had not been by Evergreen Cemetery in about seven years. My ambitions for this project were modest. On my last trip I had noticed that the lichen-encrusted fence was in disrepair and that trees were overgrown. Nothing was much changed when we arrived that Sunday morning. Jim, however, had bigger plans. He had been by a couple weeks earlier—an accidental trip brought about by confusion over the date of the proposed gathering—and had evaluated the work that needed to be done. This time he eschewed motorcycle for pickup truck, which was loaded with tools and ladder. David and Stefanie also brought rakes, clippers and the like.

On October 2, 1860, Reverend Jacob Ide of the Second Church presided over the dedication of the Sanford Monument. Reverend Ide remains the most esteemed pastor in the history of the Medway Community Church; he served from the day the doors opened at the new church until 1865, from the War of 1812 through the Civil War, a total of fifty-one years. It must have been a remarkable event. Imagine an oration given by a minister in the forty-sixth year of his pastorate to honor his immediate predecessor but one, to recognize the man whose tenure was second only to his own.

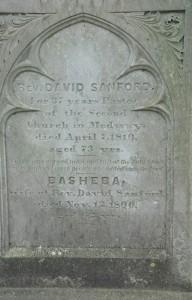

The monument, an eclectic mix of references to funerary art over the ages, became a memorial to other members of the family. A rectangular marker with carved gothic panels on each side is set on a granite plinth. A sort of cornice provides a transition or stylobate on which rests a fluted column surmounted by a draped urn with a decorative finial. As decades passed, other names were added to that of the Reverend David Sanford and his wife Bathsheba Ingersoll: a son, grandsons, spouses, great-grandchildren. (Oddly, Bathsheba is spelled “Basheba” on that panel and “Bathsheba” where she is named as Philo Sanford’s mother. I think “Basheba” is in error.) An arcade of headstones marks the resting places of various Cutlers. The stones, three hemlocks and the laurel bush all fit within the precincts of an ornate iron fence.

Tarp-loads of leaves and sticks were emptied onto the brush pile behind the cemetery dumpster. The laurel bush was pruned and the aforementioned hemlock denuded of a number of branches. When the last log was dragged away, when the ground was clean and the sagging gate rewired shut we looked at The Enclosure. When I say that it has not looked this good in a hundred years, I think that is not much of an exaggeration.

And when I say that that beautiful June Sunday spent with my family was one of the happiest in my memory, why that is not much of an exaggeration either.